The growth of the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA), the largest metropolitan region in Canada, tells an interesting story. As the region continued to add nearly 100,000 people a year, as it has for the last 20 years, it began to accommodate that growth more efficiently in the early part of the 21st century, even before policies were fully in place to support more efficient growth patterns.

In this section we explore growth between 2001 and 2011 more closely for the two patterns of urban development--intensification and greenfield development

In Figure 7, we compare the net gain in population and dwellings accommodated through greenfield development versus intensification. The majority of the net new population was accommodated through greenfield development, even though the newly developed areas absorbed just over 50% of net new dwellings. And while nearly half of net new dwellings were located in the existing urban footprint, this area accommodated only 14% of population growth.

Figure 7: Net gain in population and dwelling in the GTHA, 2001-2011

NOTE: Due to rounding, totals may differ from subregional totals.

Our analysis measures only net changes in population and dwelling stock, which means we account for both gain and loss of population and dwellings in a single figure. This matters most for intensification, which is measured in urban areas where there is existing housing and population. For example, while the urban areas in the GTHA have added new residents, these areas also lost residents who moved away or died as neighbourhoods matured. Our maps in the intensification discussion illustrate the losses and gains in urban neighbourhoods in more detail.

It is also interesting to note the wide gap between the number of people and the number of dwellings being added through intensification versus those added through greenfield development. In the existing urban areas, there was a larger net gain in dwellings than in population; the opposite pattern occurred for greenfield development. The difference indicates that different household sizes are being accommodated in different parts of the region.

Greenfield growth in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area

Figure 8: Greenfield areas urbanized, GTHA, 2001-2011

[NOTE: The area highlighted in magenta represents the greenfield area in the GTHA. All numbers in this section have been measured within this area.]

Between 2001 and 2011, 86% of the population growth in the GTHA was accommodated through greenfield development.

While greenfield development accounted for 54% of the dwellings, 86% of the population growth was accommodated in the newly built area of the GTHA between 2001 and 2011 (shown in magenta on Figure 8). The difference between the numbers of population and those of dwellings added indicates that larger households are being accommodated through greenfield development.

Figure 9: Dwelling types added in greenfield area, GTHA, 2001-2011

When we look at the dwelling stock, we find that these larger households are being accommodated in ground-related housing, mostly single-detached houses (see Figure 9). In the GTHA, greenfield development has traditionally delivered larger dwellings to accommodate families with children. Our findings show that this continues to be the case. The average household size accommodated through greenfield development between 2001 and 2011 is 3.4 persons per household compared to the region's average of 2.65.

Table 4: Population and dwellings added in greenfield area and urban expansion, 2001-2011

| Population added to greenfield area | Proportion of population growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of GTHA greenfield population growth (%) | Dwellings added to greenfield area | Proportion of all dwelling growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of GTHA greenfield dwelling growth (%) | Urban expansion (hectares) | Percent area increase for municipality (%) | Proportion of GTHA urban expansion (%) |

City of Toronto | 25,540 | 19 | 3 | 7,570 | 5 | 3 | 300 | 1 | 2 |

Peel Region | 293,760 | 95 | 34 | 75,360 | 73 | 30 | 5,040 | 15 | 34 |

York Region | 260,850 | 86 | 30 | 76,240 | 72 | 31 | 4,180 | 14 | 28 |

Durham Region | 109,940 | 100 | 13 | 36,160 | 81 | 15 | 1,560 | 9 | 10 |

Hamilton | 36,500 | 100 | 4 | 12,360 | 61 | 5 | 1,160 | 8 | 8 |

Halton Region | 131,280 | 100 | 15 | 41,490 | 91 | 17 | 2,750 | 19 | 18 |

TOTAL | 857,870 |

|

| 249,180 |

|

| 14,990 |

|

|

NOTE: Population and dwellings added in greenfield area and urban expansion, GTHA, 2001-2011

Table 4 provides a summary of greenfield development statistics for the six upper- and single-tier municipalities in the GTHA.[1] The Growth Plan requires upper- and single-tier municipalities to direct 40% of new residential development to the existing urban area. Given this intensification target, one might assume that greenfield development would make up the other 60%. Our findings, however, show that between 2001 and 2011, 905 municipalities were growing mainly through greenfield development.[2] With the exception of the Cities of Toronto and Hamilton, these municipalities did not achieve the target of 40% intensification between 2001 and 2011. The Regional Municipality of Halton had the highest proportion of greenfield development at 91%, followed by Durham (81%), York (72%), Peel (73%), and Hamilton (61%). The City of Toronto had minimal greenfield development, located in the northeast (the only part of the City that is not already fully built out).

Four municipalities account for almost half of the overall greenfield development in the GTHA: Brampton, Vaughan, Mississauga, and Markham.

As our findings show, suburban municipalities in the Toronto region continued to focus on greenfield development between 2001 and 2011--such momentum is difficult to break. In political science literature, the concept of path dependence is used to describe the difficulty of departing from an institution's long-standing policy choices and their consequences (Taylor and Burchfield 2010). It is clear that shifting away from planning for greenfield development will be difficult for many suburban municipalities, given their predominant form of historical development.

When we examine greenfield patterns at the lower-tier municipality level, we find that a few lower-tier municipalities in Peel and York Regions were the main contributors to dwellings added through greenfield development, accounting for almost 50% of the overall greenfield development in the GTHA--Brampton (20%), Vaughan (10%), Mississauga (9%), and Markham (9%). In 10 years, Brampton alone added 50,000 dwellings through greenfield development and accommodated more than 200,000 people in these newly developed areas.

These same municipalities also had some of the highest average household sizes; Brampton had the highest, at 3.9 persons per household in the greenfield expansion area (see Appendix B for lower-tier numbers).

When we examine rates of urban expansion, we find that over half of the newly urbanized land in the GTHA is in Peel and York. Once again, Brampton, Vaughan, Mississauga, and Markham were the main contributors to urban expansion. In Markham, our findings show that land was used more efficiently over the 10-year period than in the other large, fast-growing municipalities. Markham's urban footprint contributed to less than 6% of the GTHA's urban area expansion, while its growth in dwellings contributed to 9% of the region's greenfield dwellings, resulting in a more efficient use of land in Markham than in Brampton, Vaughan, or Mississauga.

Net new population absorbed in the existing urban area in the GTHA was a mere 14% of the total population added to the region.

Although the proportion of different types of housing stock remained much the same between the two decades, our findings show that land was being used more economically in this period, since the growth rate in dwellings and population held steady, while the rate of growth of the urban area slowed down in the latter decade. This means that housing was being built more densely than it had been through the 1990s, while continuing to accommodate larger households.

Municipalities like Markham show evidence of even more compact greenfield development compared with other large, fast-growing, lower-tier municipalities. Markham was an early adopter of "New Urbanist" planning policies, an approach that emphasizes "mixed use, mixed housing types, compact form, an attractive public realm, pedestrian-friendly streetscapes, defined centres and edges and varying transportation options" (Grant 2006, p. 8). Our findings show that a change in Markham's planning approach distinguishes its growth patterns from those of its neighbouring suburban municipalities.

Intensification in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area

Figure 10: Intensification area, GTHA

[Note: The 2001 urban area is shown in magenta. Population and dwelling numbers reported for intensification are measured within this area.]

The geographic area in which we measure intensification is much larger than the area in which we measure greenfield development. Our method for calculating intensification yields the net changes in population and dwellings for the area highlighted in Figure 10. Unlike the urban expansion area where greenfield development takes place, there was a substantial population and dwelling stock pre-existing in the built-up urban area prior to 2001. Our method allows us to show how that stock has changed and how many people have been added or lost overall, but it does not allow us to specify how many people went specifically into new or pre-existing dwellings. People may move into an area and occupy new or pre-existing dwellings; others may move out. We can only measure the overall net change of a specific geographic area at the end of the decade (2001-2011).

However, calculating the net gain and loss of population and dwellings is informative. Our analysis indicates that the net new population absorbed in the existing urban area in the region, an area of more than 157,000 hectares, was a mere 14% of the total population added to the region. This is a small fraction of new residents to the GTHA, even though almost half of all new dwellings were created in this same area. Again, we see a big gap between the addition of dwellings and population in the existing urban area. Our analysis shows that this gap is partially due to population losses in established urban neighbourhoods that offset population gains through intensification.

The decline in average household size, while an observed trend across Canada, is especially visible in existing urban areas of the GTHA. Household size in this area declined from 2.74 to 2.52 in a 10-year period. Declining household size in existing urban areas undoubtedly reflects demographic changes in established urban areas--an aging population, a lower birth rate, delayed child-bearing, and generally an increase in the number of single-headed and single-person households. Our analysis provides only a snapshot in time, but declining household size and the gap between the net gain in population and dwellings have large impacts on planning in the region. Below we discuss where population loss is happening within the established urban areas in the region.

Hamilton, Halton, and Durham experienced a net loss of population in their existing urban areas between 2001 and 2011.

Population gain and loss in the existing urban area

Not surprisingly, the City of Toronto gained the most net new residents through intensification, more than 100,000 people over 10 years. York gained just of 13% of its net new residents through intensification while Peel gained only 4%. However, what is surprising is that three of the five suburban municipalities experienced net losses. Hamilton, Halton, and Durham all experienced a net loss in population in their existing urban areas between 2001 and 2011, even though there was a net gain in dwellings (see Table 5).

Table 5: Population and dwelling change, GTHA intensification area, 2001-2011

Population change in intensification area | Proportion of population growth in municipality (%)* | Proportion of GTHA intensification population growth (%)* | Dwellings added to intensification area | Proportion of dwelling growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of GTHA intensification dwelling growth (%) | |

City of Toronto | 108,030 | 81 | 67 | 134,730 | 95 | 64 |

Peel Region | 12,710 | 4 | 8 | 27,180 | 26 | 13 |

York Region | 40,020 | 13 | 25 | 27,250 | 26 | 13 |

Durham Region | -7,860 | - | - | 7,790 | 17 | 4 |

Hamilton | -5,940 | - | - | 7,840 | 38 | 4 |

Halton Region | -4,720 | - | - | 4,140 | 9 | 2 |

TOTALS | 160,760 |

|

| 208,930 |

|

|

NOTE: The proportion of population growth through intensification for the GTHA does not include the loss in population in the 2001 existing urban area.

Although the City of Toronto and the Regions of Peel and York experienced a net gain in both population and dwellings through intensification, there was a net loss in certain established urban areas across these municipalities (see Figure 11). This is an important finding that we refer to as "running hard to stand still." Existing urban areas contain (hard and soft) services that are already in place. But in many areas, population has declined, while an ever-increasing number of new residents are accommodated in greenfield developments. These new areas require investment in new services and infrastructure while existing infrastructure in the already built-up areas is serving fewer people.

A striking example can be found in the suburb of Brampton. While Brampton gained more than 200,000 new residents through greenfield development, it experienced a net loss of population in its existing urban area (see Appendix B for results for lower-tier municipalities). The loss signals changing demographics that need to be considered. As the suburban municipalities in the GTHA mature, there is a need to understand the internal dynamics of each municipality as it plans for future growth.

Figure 11 illustrates where the net loss is occurring within the region. In addition to Brampton, large parts of the Cities of Toronto, Mississauga, Oshawa, Whitby, and Hamilton are experiencing a net loss of population in certain established areas.

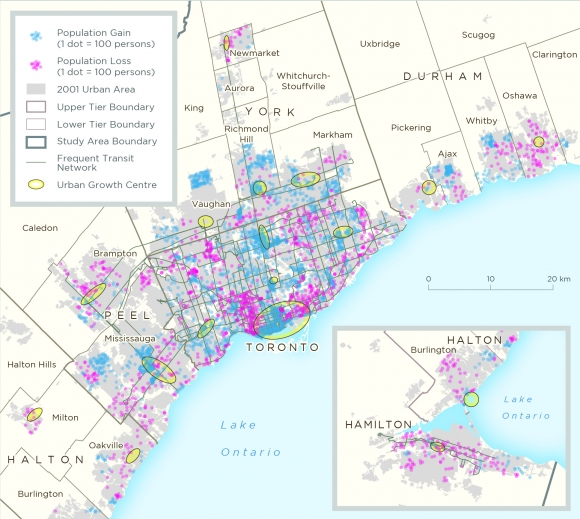

Figure 11: Population gain and loss in established urban areas, GTHA, 2001-2011

NOTE: The dots on the map represent approximate locations. The map uses a dot density technique to illustrate clusters of population loss or gain. The dots have been placed randomly within census tracts, although the boundaries of census tracts are not shown in order to illustrate other data layers more clearly.

The same large, fast-growing municipalities that contributed the most to greenfield development also contributed the most to intensification: Mississauga, Markham, and Vaughan.

Dwelling gain in the existing urban area

Figure 12 shows the spatial distribution of new dwellings added through intensification. There was an overall net gain of dwellings in the existing urban area. It comes as no surprise that the City of Toronto accounted for the lion's share (64%) of the GTHA's new dwellings added through intensification (see Table 5). Peel and York each accounted for about 13% of the GTHA's dwellings gained through intensification, while Hamilton, Halton, and Durham contributed a minimal amount.

Figure 12: Dwelling added through intensification, GTHA, 2001-2011.

growingcities3_map9_final_02-01.jpg

NOTE: The dots on the map represent approximate locations. The map uses a dot density technique to illustrate clusters of dwellings. The dots have been placed randomly within census tracts, although the boundaries of census tracts are not shown in order to illustrate other data layers more clearly.

At the lower-tier level, the same large, fast-growing municipalities in the 905 area that contributed the most to greenfield development also contributed the most to intensification--Mississauga, Markham, and Vaughan. Mississauga on its own contributed 10% of the region's overall dwelling intensification rate (see Appendix B for results for lower-tier municipalities).

A net gain in dwellings brought about changes to the composition of the housing stock in the existing urban area. The region lost about 43,000 single-detached houses through demolition, conversion, or redevelopment. Most of the newly added units were in the form of apartments (see Figure 13), with the remaining 22% being attached, ground-related units. The size of the units gained through intensification of the existing urban area contributed to a change in household size. As the average household size in the existing urban area continued to shrink over the 10-year period from 2.74 to 2.52, it appears that the new units did not accommodate larger households and that households in the existing housing stock continued to shrink.

Figure 13: Dwelling types added through intensification, GTHA, 2001 - 2011

Population and Dwelling Change in Urban Growth Centres and Frequent Transit Service Areas

The Growth Plan identifies 25 Urban Growth Centres, of which 17 are in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. Figure 12 illustrates the spatial distribution of the net new dwellings in the existing urban area across the region and indicates the approximate location of the Urban Growth Centres. The map also shows corridors with frequent transit service (see Appendix A for the process used to identify FTNs and Appendix C for the Dissemination Areas included in the analysis).

Of the GTHA's growth through intensification, the Urban Growth Centres absorbed 95% of the net new residents and 44% of the net new dwellings. This is superficially a good-news story from the perspective of policy-making. People use infrastructure and services, which means that population growth through intensification is best placed in the region's urban growth centres, which typically have better access to transit and existing services.

However, if we look at the GTHA's overall growth, including growth through greenfield development, the Urban Growth Centres absorbed only 13% of the net new residents and 20% of the net new dwellings due to the extraordinary amount of growth that went to the greenfield areas.

Figure 12 shows that within the City of Toronto, most of the new dwellings are clustered in the City's core and the area immediately to its west, including the Liberty Village redevelopment area. There is also a substantial cluster of net new dwellings near the North York Centre at the intersection of the Yonge and Sheppard subway lines. In the 905 area, the most apparent cluster is near Mississauga City Centre.

Table 6 breaks down the net new residents and dwellings across the 17 Urban Growth Centres. The table confirms what is depicted in the maps: that 75% of the population and dwelling growth in centres went to only three centres--Downtown Toronto, North York Centre, and Mississauga City Centre. Downtown Toronto gained the largest amount of dwellings and population (44,000 units and 53,000 people between 2001 and 2011). Many of the Urban Growth Centres had little or no intensification.

Table 6: Population and dwelling change in intensification area, GTHA, 2001-2011

Population 2001 | Dwellings 2001 | Population 2011 | Dwellings 2011 | Population change 2001-11 | Dwelling change 2001-11 | % population change | % dwellings change | Proportion of population growth in centres (%) | Proportion of dwellings growth centres (%) | Proportion of GTHA population growth (%) | Proportion of GTHA dwelling growth (%) | |

Toronto: Downtown | 157,310 | 87,480 | 209,770 | 131,260 | 52,460 | 43,780 | 33 | 50 | 41 | 49 | 5 | 10 |

Mississauga City Centre | 60,380 | 23,600 | 79,780 | 34,850 | 19,400 | 11,250 | 32 | 48 | 15 | 13 | 2 | 2 |

Toronto: North York | 36,570 | 16,840 | 63,830 | 32,060 | 27,260 | 15,200 | 75 | 90 | 21 | 17 | 3 | 3 |

Toronto: Yonge-Eglinton Centre | 15,550 | 10,260 | 19,870 | 13,220 | 4,320 | 2,960 | 28 | 29 | 3 | 3 | <1 | 1 |

Downtown Brampton | 14,910 | 6,170 | 16,340 | 8,020 | 1,430 | 1,850 | 10 | 30 | 1 | 2 | <1 | <1 |

Toronto: Etobicoke Centre | 13,980 | 6,300 | 18,950 | 9,310 | 4,970 | 3,010 | 36 | 48 | 4 | 3 | <1 | 1 |

Downtown Burlington | 12,190 | 6,530 | 13,420 | 7,320 | 1,230 | 790 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Richmond Hill/Langstaff | 10,450 | 3,480 | 16,900 | 6,240 | 6,450 | 2,760 | 62 | 79 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

Toronto: Scarborough Centre | 9,800 | 4,090 | 19,970 | 9,280 | 10,170 | 5,190 | 104 | 127 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

Downtown Pickering | 9,140 | 3,520 | 8,960 | 3,760 | -180 | 240 | -2 | 7 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

Downtown Hamilton | 8,640 | 5,180 | 9,440 | 5,700 | 800 | 520 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Downtown Oshawa | 8,060 | 4,030 | 7,860 | 4,180 | -200 | 150 | -2 | 4 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Downtown Milton | 4,620 | 1,850 | 4,890 | 2,190 | 270 | 340 | 6 | 18 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

Markham Centre | 3,550 | 1,050 | 9,490 | 4,300 | 5,940 | 3,250 | 167 | 310 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Newmarket Centre | 2,290 | 750 | 2,230 | 830 | -60 | 80 | -3 | 11 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

Vaughan Metropolitan Centre | 2,060 | 620 | 2,130 | 640 | 70 | 20 | 3 | 3 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Midtown Oakville | 1,100 | 390 | 1,320 | 600 | 220 | 210 | 20 | 54 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

TOTALS | 370,586 | 182,132 | 505,148 | 273,749 | 134,562 | 91,617 | 36 | 50 | - | - | 13 | 20 |

The centres experiencing the greatest percentage change between 2001 and 2011 were the suburban Scarborough Town Centre and Markham Centre. Although these two UGCs contributed about 10% of the intensification in all UGCs, they experienced the greatest transformation relative to their state in 2001. Markham Centre's population grew by 167% and its dwellings by 310%, and Scarborough City Centre's population grew by 104% and its dwellings by 127%.

In addition to the UGCs, we examined population and dwelling change in frequent transit corridors and near GO Train stations. Since the geography of these areas overlaps the 2001 existing urban area and the 2011 urban expansion area, we measured how much of the GTHA's net new population and dwellings coincided with the station areas. Although GO Train service is currently focused on the a.m./p.m. peak commute, the service is slowly being transformed to more frequent service and is expected to offer 15-minute, all-day service by 2025. Currently many GO stations are surrounded by parking lots.

Table 7: Population and dwellings added near frequent transit network (FTN) and GO Stations, GTHA, 2001-2011

| Added near FTN | % of total change | Added near GO stations | % of total change |

Population | 181,390 | 18 | 104,600 | 10 |

Dwellings | 171,820 | 37 | 48,500 | 11 |

Between 2001 and 2011, 18% of the region's net new population and 37% of the net new dwellings were accommodated in frequent transit areas (see Table 7). As can be seen in Figure 12, the majority of the frequent transit lines are located in the City of Toronto, where service is provided by the TTC. The large gap between net new population and dwellings is likely because the frequent transit corridors are in the established urban areas in the City that have experienced net population loss. The gap matters, because it is people who ride transit, not dwellings.

Given that the Ontario Government's transit priority of the next 10 years is to invest in the transformation of the GO train service, it is important to understand the development potential of the areas around GO stations. Some are embedded within the existing urban area and others are surrounded by parking lots and in low-density industrial areas. When we measure growth around GO station areas, we find that 10% of the GTHA's net new population and 11% of the region's dwellings were accommodated within one kilometre of a GO Station. This percentage could be increased in future years, given the development potential in converting parking surfaces and large lots near many of the GO stations to more intensified urban uses.

Urban Growth Centres in the GTHA absorbed only 13% of the net new residents and 20% of the net new dwellings between 2001 and 2011.

[1] Statistics for the lower-tier municipalities can be found in Appendix A.

[2] The suburban municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area and Hamilton outside the City of Toronto are colloquially referred to as the "905," for their telephone area code.