The Vancouver region has a longer and more consistent history of managing growth than the Toronto region. The approach has been to concentrate growth with the ultimate goal of maintaining a compact urban form. It should therefore come as no surprise that in both decades under study, the vast majority of the region's growth was through intensification rather than greenfield development.

Between 2001 and 2011, the region's urban area increased by a mere 4%, while its regional population increased by 16% and its dwellings by 21%. Unlike the GTHA, the existing urban area accommodated the majority of the net gain in both population (69%) and dwellings (76%).

Figure 14: Net gain in population and dwellings, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

neptis_piecharts_fig14_may26.jpg

NOTE: Due to rounding, totals may differ from subregional total.

In the Vancouver region, there was a larger net gain in population compared with dwellings for greenfield development, and a larger net gain in dwellings compared with population in the existing urban area. Although similar gaps were identified in the GTHA, the gaps are much smaller in Metro Vancouver than in the Toronto region, indicating that household sizes in the Vancouver region are more evenly balanced between the existing urban areas and the new expansion areas (see Figure 14).

Between 2001 and 2011, the urban area of Metro Vancouver increased by a mere 4% while its regional population increased by 16% and its dwellings by 21%.

Greenfield growth in Metro Vancouver

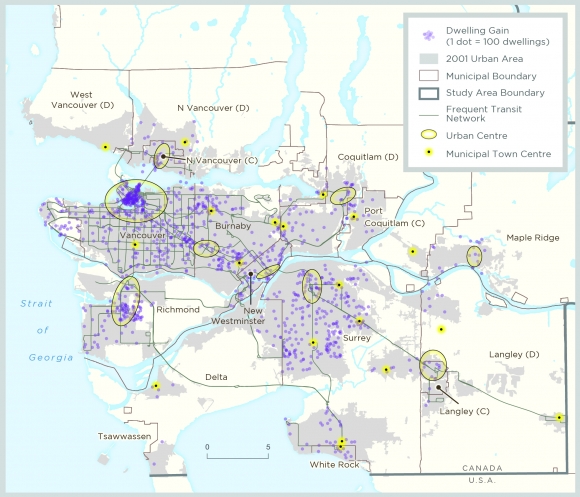

Metro Vancouver's urban expansion between 2001 and 2011 is shown in Figure 15. These small areas accommodated 31% of the region's population growth and 24% of the region's dwelling gain.

Figure 15: Greenfield areas urbanized, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

[Note: The area highlighted in magenta represents the greenfield area in Metro Vancouver. All numbers in this section have been measured within this area.]

As in the Toronto region, suburban greenfield development in the Vancouver region has traditionally accommodated larger households in larger dwelling units. The average household size in the new urban area is larger than the regional average, 2.65 compared with 2.43.

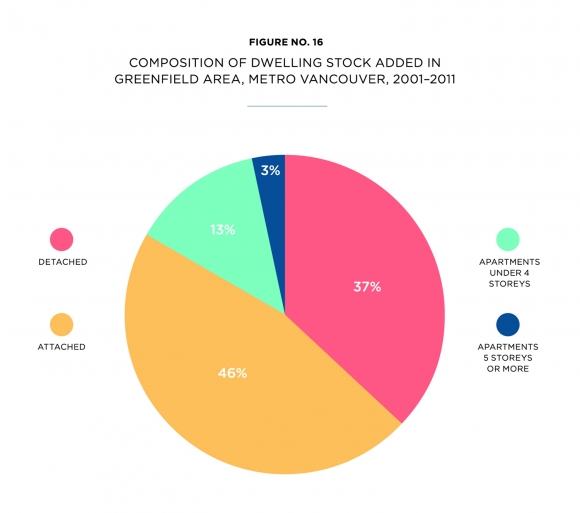

The housing stock for Metro Vancouver's greenfield development is mainly ground-related housing, although with a much higher percentage of attached dwellings than the GTHA and a sizable proportion of mid-rise apartments (see Figure 16).

Figure 16: Dwelling types added in greenfield area, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

Most of the region's urban expansion took place in the suburban municipalities of Surrey, Langley, Richmond, and Maple Ridge.[1] But the majority of the region's population and dwelling growth in greenfield areas was accommodated in Surrey, Langley, and Maple Ridge. Although Richmond contributed to the region's urban expansion, it did not add much population or dwellings through greenfield growth. This is likely due to Richmond's role as an employment-rich municipality. Growth in employment is captured only by our measure of urban expansion, not in the census data used for this study.

The region's total greenfield growth consists of just under 102,000 people and 40,000 dwellings (see Table 8). It is interesting to note that these numbers represent less than half the population growth and about four-fifths of the dwellings added through greenfield development in the City of Brampton, one lower-tier municipality in the GTHA.

Table 8: Population and dwellings added in greenfield area and urban expansion, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

Population added in greenfield area | Proportion of population growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver green-field population (%) | Dwellings added in green-field area | Proportion of all dwelling growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver greenfield dwelling growth (%) | Total urban expansion (hectares) | Percent of urban expansion in municipality (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver urban expansion (%) | |

Burnaby | 2,280 | 8 | 2 | 1,200 | 8 | 3 | 20 | 0 | 1 |

Coquitlam | 6,260 | 46 | 6 | 2,450 | 37 | 6 | 65 | 2 | 3 |

Delta | 480 | 17 | 0.5 | 190 | 8 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 1 |

Langley | 18,050 | 96 | 18 | 6,820 | 66 | 18 | 500 | 11 | 25 |

Maple Ridge | 12,010 | 93 | 12 | 3,980 | 66 | 10 | 100 | 5 | 5 |

New Westminster | 1,710 | 15 | 2 | 600 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

N. Vancouver | 390 | 6 | 0.4 | 190 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Pitt Meadows | 2,030 | 66 | 2 | 780 | 48 | 2 | 40 | 7 | 2 |

Port Coquitlam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Port Moody | 7,650 | 84 | 8 | 3,170 | 75 | 8 | 60 | 6 | 3 |

Richmond | 130 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 90 | 1 | 0 | 170 | 3 | 8 |

Surrey | 46,070 | 36 | 45 | 16,510 | 36 | 43 | 910 | 6 | 46 |

Vancouver | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

W. Vancouver | 1,340 | 74 | 1 | 630 | 37 | 2 | 30 | 1 | 2 |

White Rock | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Other | 3,340 | 52 | 3 | 1,680 | 57 | 4 | 85 | 8 | 4 |

TOTALS | 101,740 |

|

| 38,290 |

|

| 1,916 |

|

|

NOTE: The "Other" category includes non-municipal jurisdictions such as the endowment lands owned by the University of British Columbia.

Intensification growth in Metro Vancouver

The vast majority of population and dwellings added in Metro Vancouver took the form of intensification. More than 223,000 people and 123,000 units were absorbed into the existing urban area, a total area of 67,800 hectares (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: Intensification area, Metro Vancouver

[NOTE: The 2001 urban area is highlighted in magenta. All numbers in this section have been measured within this area.]

Household size in the existing urban area decreased between 2001 to 2011 from 2.5 to 2.4, following the general trend in Canada. However, the composition of the new housing stock in the existing urban area represents a different mix from that in the GTHA. The majority is in the form of attached ground-related housing, with the rest of the stock almost evenly split between mid- and high-rise apartments (see Figure 18). The region lost more than 39,000 single-detached homes in the existing urban area, a similar number to the decline observed in the GTHA (43,000 units), but within a much smaller urban area, 67,800 versus 157,300 hectares.

Figure 18: Dwelling types added through intensification, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

Population gain and loss in the existing urban area

Figure 19 illustrates the spatial distribution of the net population loss and gain across Metro Vancouver and Table 9 shows the amount and percentage of population change in the existing urban areas for all municipalities in Metro Vancouver.

There has been a net population gain in all but two municipalities in Metro Vancouver; the exceptions are West Vancouver and Langley, which experienced a very small loss of population. The map shows that established urban areas in the Vancouver region have not experienced much population loss. Despite some population loss in the City of Vancouver, the loss is not as noticeable as that observed in the City of Toronto or other urban areas in the GTHA. Although the Vancouver region is presumably experiencing similar demographic shifts as those in the Toronto region, since the trends are Canada-wide, these shifts are not resulting in large overall losses of population within the urbanized area, presumably because of the higher rate of intensification.

Figure 19 also indicates that the majority of the net new population went to the existing urban areas of Surrey, City of Vancouver, Richmond, and Burnaby, with the largest number of net new residents going to Surrey's established urban areas, about 74,000 people or 23% of the region's entire new population growth in ten years. By 2040, the population in the City of Surrey is projected to be on a par with the population of the City of Vancouver. Surrey is taking advantage of this growth through the massive redevelopment of Surrey Metro Centre that includes an integrated district energy centre that will eventually be fuelled by renewable sources of energy (Giratalla and Owen 2014).

Figure 19: Population gain and loss in established urban areas, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

(Note: The dots on the map represent approximate locations. The map uses a dot density technique to illustrate clusters of population loss or gain. The dots have been placed randomly within census tracts, although the boundaries of census tracts are not shown in order to illustrate other data layers more clearly.)

Table 9. Population and dwelling change, Metro Vancouver intensification area, 2001-2011

Population change in intensification area | Proportion of population growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver population added through intensification (%) | Dwellings added to intensification area | Proportion of dwellings growth in municipality (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver dwellings added through intensification (%) | |

Burnaby | 27,020 | 92 | 12 | 13,970 | 92 | 11 |

Coquitlam | 7,860 | 58 | 4 | 4,150 | 63 | 3 |

Delta | 2,430 | 83 | 1 | 2,300 | 95 | 2 |

Langley | -80 | - | - | 2,930 | 28 | 2 |

Maple Ridge | 1,030 | 8 | 0.5 | 1,920 | 32 | 2 |

New Westminster | 9,610 | 85 | 4 | 5,380 | 90 | 4 |

North Vancouver | 6,520 | 98 | 3 | 5,320 | 97 | 4 |

Pitt Meadows | 460 | 15 | 0.2 | 500 | 31 | 0.4 |

Port Coquitlam | 5,090 | 100 | 2 | 3,290 | 100 | 3 |

Port Moody | 1,510 | 16 | 1 | 1,050 | 25 | 1 |

Richmond | 26,000 | 100 | 12 | 12,810 | 99 | 10 |

Surrey | 74,370 | 62 | 33 | 28,950 | 64 | 23 |

Vancouver | 57,830 | 100 | 26 | 37,760 | 100 | 30 |

West Vancouver | 460 | 26 | 0.2 | 1,070 | 63 | 1 |

White Rock | 1,090 | 100 | 0.5 | 1,100 | 100 | 1 |

Other | 2,620 | 41 | 1 | 1,360 | 41 | 1 |

TOTALS | 223,820 |

|

| 123,860 |

|

|

Note: The other category includes non-municipal jurisdictions such as the endowment lands owned by the University of British Columbia.

Dwelling gain in the existing urban area

Figure 20 shows that the spatial distribution of the net new dwellings absorbed into the existing urban area parallels the pattern of population gain in Figure 19. The same four municipalities (the Cities of Vancouver, Surrey, Richmond, and Burnaby) contributed to the majority of the region's net new dwellings added through intensification.

Figure 20: Dwellings added through intensification, Metro Vancouver, 2001-2011

(Note: The dots on the map represent approximate locations. The map uses a dot density technique to illustrate clusters of dwellings. The dots have been placed randomly within census tracts, although the boundaries of census tracts are not shown in order to illustrate other data layers more clearly.)

In the next section, we examine how much of the intensification went into urban centres and near frequent transit service in Metro Vancouver.

Population and Dwelling Change in Urban Centres and Frequent Transit Service Areas

In 2011, Metro Vancouver's regional growth strategy introduced a hierarchy of urban centres. Eighteen municipal town centres (MTCs) were identified in addition to the nine regional town centres referenced in earlier regional plans, for a total of 27 centres. By 2041, 40% of the region's dwelling growth is expected to be directed to these centres, up from 26% as measured in 2006.

Our analysis estimates that 36% of the region's net new population and 27% of dwellings were absorbed in the 27 centres between 2001 and 2011. If we limit the analysis to the original nine centres as identified by the ovals in Figures 19 and 20, we find that these historical centres absorbed about one-quarter of the region's net new population and dwellings.

Table 10 indicates that of the net new population and dwellings added to the region's 27 centres, the bulk of the growth went to Metro Core (30% of population and 32% of dwellings) in the City of Vancouver and Richmond Centre (15% of population and 14% of dwellings). These two centres alone absorbed about 17% of the Metro Vancouver's net new population and dwellings. Both centres are located on the Canada Line, a rapid transit line that opened in the summer of 2009 connecting Metro Core to the airport in Richmond. The municipality of Richmond has traditionally been a net importer of commuters (more daily commuters travel into the municipality than leave it), and in 2006, Richmond had a higher activity rate (ratio of jobs to population) than the regional average (0.71 versus 0.52). Increasing the population living along the Canada Line in Richmond would allow more residents better access to the employment opportunities in the region.

Table 10: Population and dwelling change, Metro Vancouver urban centres, 2001-2011

| Population 2001 | Dwellings 2001 | Population 2011 | Dwellings 2011 | Population change 2001-11 | Dwellings change 2001-11 | Proportion of population change (%) | Proportion of dwellings change (%) | Proportion of population growth in all centres (%) | Proportion of growth in dwellings for all centres (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver population growth (%) | Proportion of Metro Vancouver growth in dwellings (%) |

Metro Core | 135,690 | 89,810 | 170,620 | 108,990 | 34,930 | 19,180 | 26 | 21 | 30 | 32 | 11 | 12 |

Surrey Metro Centre | 18,230 | 8,300 | 23,760 | 11,720 | 5,530 | 3,420 | 30 | 41 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

Regional City Centres | ||||||||||||

Richmond City Centre | 36,320 | 15,720 | 54,340 | 24,280 | 18,020 | 8,560 | 50 | 54 | 15 | 14 | 6 | 5 |

Metrotown | 26,880 | 13,660 | 28,960 | 14,500 | 2,080 | 840 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Lonsdale | 26,040 | 14,000 | 28,890 | 16,310 | 2,850 | 2,310 | 11 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Langley Town Centre | 17,380 | 8,490 | 27,950 | 13,250 | 10,570 | 4,760 | 61 | 56 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 3 |

Coquitlam Town Centre | 13,530 | 6,350 | 16,430 | 7,620 | 2,900 | 1,270 | 21 | 20 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Maple Ridge Town Centre | 12,350 | 5,910 | 14,020 | 7,190 | 1,670 | 1,280 | 14 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

New Westminster Downtown | 9,520 | 5,480 | 13,580 | 7,750 | 4,060 | 2,270 | 43 | 41 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Municipal Town Centres | ||||||||||||

Edmonds | 22,990 | 9,810 | 31,850 | 13,970 | 8,860 | 4,160 | 39 | 42 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

Lougheed Burnaby | 13,630 | 6,340 | 16,140 | 7,440 | 2,510 | 1,100 | 18 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Guildford | 11,250 | 5,160 | 14,180 | 6,260 | 2,930 | 1,100 | 26 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Ambleside | 8,280 | 5,090 | 9,200 | 5,680 | 920 | 590 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Fleetwood | 8,010 | 2,920 | 13,640 | 4,630 | 5,630 | 1,710 | 70 | 59 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Pitt Meadows | 7,730 | 3,110 | 7,930 | 3,430 | 200 | 320 | 3 | 10 | <1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Newton | 7,610 | 3,060 | 7,810 | 3,220 | 200 | 160 | 3 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Port Coquitlam | 6,500 | 3,000 | 8,380 | 4,120 | 1,880 | 1,120 | 29 | 37 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Lougheed Coquitlam | 6,330 | 2,720 | 7,150 | 3,250 | 820 | 530 | 13 | 19 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

South Surrey (Semiahmoo) | 6,120 | 3,160 | 6,850 | 3,600 | 730 | 440 | 12 | 14 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Oakridge | 5,650 | 2,430 | 6,130 | 2,540 | 480 | 110 | 8 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Lynn Valley | 5,490 | 2,170 | 6,210 | 2,600 | 720 | 430 | 13 | 20 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Ladner | 5,300 | 2,280 | 5,540 | 2,450 | 240 | 170 | 5 | 7 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

Brentwood | 5,210 | 2,430 | 11,680 | 5,790 | 6,470 | 3,360 | 124 | 138 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

Inlet Centre | 4,410 | 1,670 | 5,440 | 2,350 | 1,030 | 680 | 23 | 41 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Aldergrove | 4,090 | 1,580 | 3,900 | 1,700 | -190 | 120 | -5 | 8 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

Cloverdale | 2,660 | 1,320 | 2,660 | 1,470 | 0 | 150 | 0 | 11 | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

White Rock | 2,150 | 1,550 | 2,770 | 1,990 | 620 | 440 | 29 | 28 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

Willoughby | 1,190 | 410 | 930 | 350 | -260 | -60 | -22 | -15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

TOTALS | 430,540 | 227,930 | 546,940 | 288,450 | 116,400 | 60,520 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTALS (except for MTCs) | 295,940 | 167,720 | 378,550 | 211,610 | 82,610 | 43,890 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Langley Centre and the Municipal Town Centres of Brentwood and Fleetwood experienced the greatest change between 2001 and 2011, even though altogether they absorbed only slightly more than 6% of the region's population growth. The change indicates the region's success in encouraging suburban municipalities to direct growth more strategically into centres.

Table 11 shows the number and percentage of the Vancouver region's net new dwellings and population located within walking distance of the Frequent Transit Network (FTN) in the region (see Figure 3 for network).[1] Frequent service offers an attractive alternative to the automobile, since transit riders on these lines do not need to consult a schedule ahead of time, given the regular service and shorter wait times. From this total, we separately isolated the net new dwellings and population located within walking distance of the SkyTrain Stations, since this service is an attractive alternative to the car, given its speed and direct access, unimpeded by traffic congestion.

Table 11. Population and dwellings added near frequent transit network (FTN) and SkyTrain Stations, 2001-2011

| Population and dwellings added near FTN | % of regional growth | Population and dwellings added near SkyTrain stations | % of regional growth |

Population | 151,530 | 47 | 74,890 | 23 |

Dwellings | 86,650 | 53 | 42,860 | 26 |

Note: Total regional growth is growth in population and dwellings through intensification and greenfield development. Growth in rural areas of Metro Vancouver is excluded from this calculation.

About 17% of Metro Vancouver's net new population and dwellings were accommodated in the City of Vancouver and Richmond Centres.

Walking distance for the purpose of this study is defined as a 500-metre buffer area around local routes (buses and streetcars with stops relatively close together) and a 1,000-metre buffer area around rapid transit stations, such as SkyTrain stations.

In Metro Vancouver, more than half of all new dwellings and nearly half of the net new population were located within walking distance of a frequent transit station and one-quarter of the new growth was within walking distance of a SkyTrain Station. This finding indicates that the integration of the region's land use and transportation plans has encouraged more transit-oriented development in the region.

Metro Vancouver's regional growth strategy calls for approximately 68% of new dwellings by 2041 to be located near frequent transit, including both Urban Centres, which are served by the FTN and other areas accessible to frequent transit. Our findings show that the region is on its way to achieving this goal.

In Metro Vancouver, nearly 50% of net new dwellings and population were located within walking distance of the frequent transit network.

[1] Although Metro Vancouver has its own frequent transit development area, the authors have calculated their own based on 2009 transit service schedules. The frequent transit network is defined as the transit lines (buses, subway, SkyTrain, light rail, streetcar, or bus rapid transit) running every 15 minutes or more frequently between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. on weekdays.

[1] Metro Vancouver has a single-tier municipal system unlike the two-tier system in the GTHA. See Taylor and Burchfield (2010) for a more detailed discussion of Metro Vancouver's municipal structure