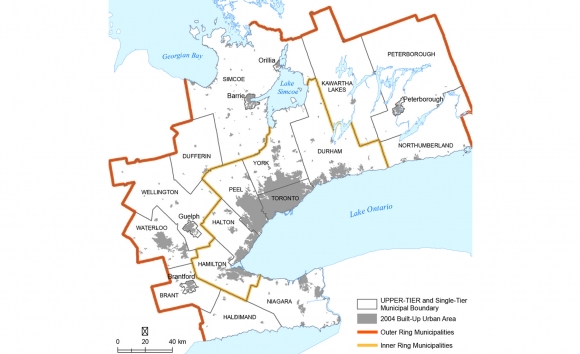

Figure 1: The Greater Golden Horseshoe

The Greater Golden Horseshoe is one of the fastest-growing metropolitan regions in the western world. [See Fig. 1.] It has taken 213 years from the establishment of the garrison at Fort York to build the present metropolis. According to government projections, almost 40% of all houses and apartment units that will exist in 2031 will have been built since 2001. Research shows that without very significant change to current automobile-dependent growth patterns, the Toronto metropolitan region will experience greatly increased environmental degradation, traffic congestion and related economic losses, and dysfunctional urban environments.

In 2005, the Neptis Foundation concluded from research that while the Greenbelt is a great public asset, only an integrated regional plan for urban growth would confront the negative effects of urban sprawl and produce a less car-dependent future in the Toronto metropolitan region. Much progress has been made by the Province toward this goal.

Since the Places to Grow discussion paper was released in the summer of 2004, the Province has released two drafts of a Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe that aim to change existing trends by intensifying existing urban areas, concentrating residents and jobs into higher-density mixed-use centres and corridors, and promoting more compact transit-supportive greenfield development. Many other important advances have also occurred, including the enactment of the new Provincial Policy Statement, the Greenbelt, and the Places to Grow Act, which for the first time in the province's history establishes a legislative base for provincial plans for metropolitan regions. The government has also released amendments to the Planning Act to make sustainable, transit-oriented, and pedestrian-friendly development a matter of provincial interest.

The government is to be commended for its vision and policy directions for the future, for its specific rejection of business-as-usual growth patterns as an acceptable option for obtaining that vision, and for its recognition that it is the proper role of the provincial government to act in the interest of the region as a whole. The Growth Plan is a once-in-a-generation event. It has been many years since the provincial government played such an active role in regional planning. [See Fig. 2] There are many possible futures. Choices made now will determine what kind of place the region will become.

The instruments proposed may be insufficient to achieve the Growth Plan's goals

Although much of the work needed to accomplish this Plan lies in the future, there are nevertheless basic weaknesses in the Growth Plan -- some technical, others more fundamental -- that we suggest need to be addressed now, since the Plan will shape future decisions and actions. The Plan is well conceived in its policy objectives and spirit of engagement, both of which are overdue. Research shows, however, that some of the ways and means the Plan proposes to reach these goals may not be up to the task.

Observations on the basis of Neptis research

To inform public debate on the Growth Plan, the Neptis Foundation is pleased to offer research-based observations and comments. The achievement of policy objectives is most likely to succeed when performance can be measured and targets are set. What is measured matters greatly. If measurements do not reflect what is happening "on the ground" or expected policy outcomes, public infrastructure investment decisions will be skewed. Neptis has focused most of its current program of research on measurable phenomena and, accordingly, this critique concentrates on the quantitative premises and targets of the proposed Growth Plan.

The commentary is grouped into four broad themes:

1. Intensification

2. Urban Growth Centres

3. Development on greenfields

4. Growth projections and change

The Province of Ontario has in the past attempted to directly manage growth in the Toronto metropolitan region -- once in the late 1960s/early 1970s and again in the early 1990s. As University of Toronto historian Richard White explains in his forthcoming Neptis study of the region's planning history, neither attempt had much effect. The 1970s effort, which began with a regional transportation study and culminated in the well-known Toronto-Centred Region concept, yielded a bold, if overaggressive, conceptual plan for the region, but only a few of its features were ever implemented. The 1990s initiative, through the Province's short-lived Office of the GTA, never got beyond concepts and visions. The region's only effective regional planning body, White argues, was the Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board of the 1950s and 1960s, a body created (but not run) by the provincial government. Although it too had difficulties implementing its plan, its key principle of maintaining contiguity of the urban area, first introduced in 1959, was adopted and still largely guides the region's growth. Regional planning is evidently not an easy job. As the Province takes on the challenging task yet again, for the first time in nearly a generation, it might do well to consider what worked and did not work in the past.

Fig. 2: Past efforts to plan the region have met with mixed success