Residential intensification is a centrepiece of the Plan

The Provincial government projects that the population of the Greater Golden Horseshoe will increase by 3.7 million between 2001 and 2031. Accommodating a higher proportion of this growth through intensification is a centrepiece of the Growth Plan. In the Plan, the Province generally defines intensification as any development within the existing built-up urban fabric. By this definition, intensification is the opposite of greenfield development, or development occurring on rural land outside the built-up urban area. More intensification can reduce the conversion of rural land to urban use, allow for more efficient investment in infrastructure, and increase the viability of public transit. Section 2.2.3 of the proposed Growth Plan specifies that by 2015, a minimum of 40% of all dwelling units built each year in each upper- or single-tier municipality must be located within the built-up urban area. There is no target for non-residential intensification.

Neither the Growth Plan nor its supporting documents offer research-based estimates of current intensification rates. Direct comparisons to intensification measurements and targets used in the U.K., Vancouver, and Sydney are not applicable, as different phenomena are measured in those places.1

Achieving the Plan's vision will require a very substantial shift in development patterns

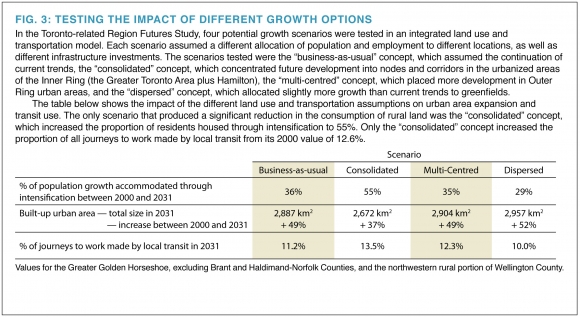

The potential impact of achieving a 40% rate of intensification on transit use and other behaviours is unknown. However, the Toronto-related Region Futures Study, undertaken for Neptis and the Province of Ontario's Smart Growth Secretariat by the IBI Group in 2003, modelled future transit use and rural land consumption under four different scenarios. This research showed that even if policies were enacted that directed a considerably higher proportion of population growth to existing urban areas, transit's share of transportation demand would rise and rural land consumption would fall by only small amounts relative to "business-as-usual." [See Fig. 3.] The simulation indicated that modest increases in intensification are likely to achieve little.

Intensification is already occurring across the region

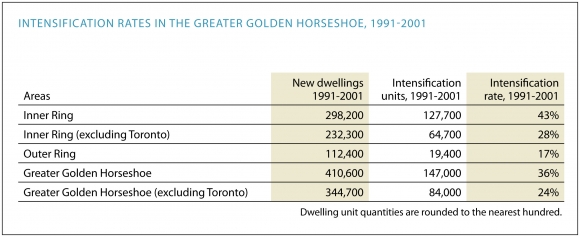

If the current rate of intensification is unknown, it is impossible to determine how close or far away different municipalities are from achieving the target. To remedy this gap, Neptis, using a method similar to that proposed by the Province, estimated average municipal intensification rates for 1991 to 2001. [See Appendix A.] In that decade, an average of about 36% of development in the Greater Golden Horseshoe was in the form of intensification. If Toronto is excluded, the intensification rate was 24%. Inner Ring municipalities recorded higher rates of intensification than those in the Outer Ring. Intensification occurred mainly in lower-tier municipalities with larger existing populations and well-established urban cores. Varying performance between one municipality and another calls the uniform 40% policy into question. While, for example, York Region achieved an average of 31% intensification between 1991 and 2001, Hamilton achieved 22%, and fast-growing Simcoe County achieved only 8%. [See Fig. 4.]

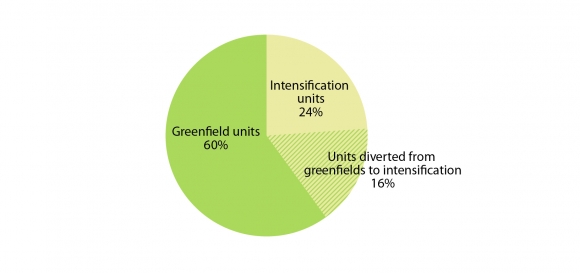

If 40% intensification were to be achieved outside the City of Toronto between 2001 and 2031, that would represent only an additional 16% of units built in that area -- 227,000 over 30 years -- being diverted from greenfields to the existing urban area. [See Fig. 5.] How much this shift would change the region's development pattern and contribute to the achievement of the Growth Plan's goals is not known. We strongly suggest that different population distribution, land use, and transportation scenarios be tested through simulation to shed light on the question of how much intensification is needed and where it should be located.

The form and location of intensification matters

Residential density on its own is not enough. To achieve the benefits of intensification, housing and workplaces must be added in sufficient quantities in the right locations and in a form conducive to transit use, walking, and cycling. Not all intensification effectively contributes to higher transit use or compact urban form. Intensification that takes the form of low-density residential infill and redevelopment of parcels dispersed throughout the urban fabric irrespective of their relationship to public transit and other infrastructure is likely to be ineffective. While this kind of intensification increases population density on each particular site, it has little impact on transit use, because these sites lack a critical mass of trip origins and trip destinations such as homes, jobs, schools, shops, and other amenities. Intensification will be most effective when it contributes to concentrated mixed-use development. Identifying appropriate sites for intensification in established urban areas can take place only in the context of a region-wide plan for investment in transportation facilities. This has not yet occurred, but is essential to the preparation and revision of local plans.

The intensification measure and target are unlikely to further the goals of the Plan

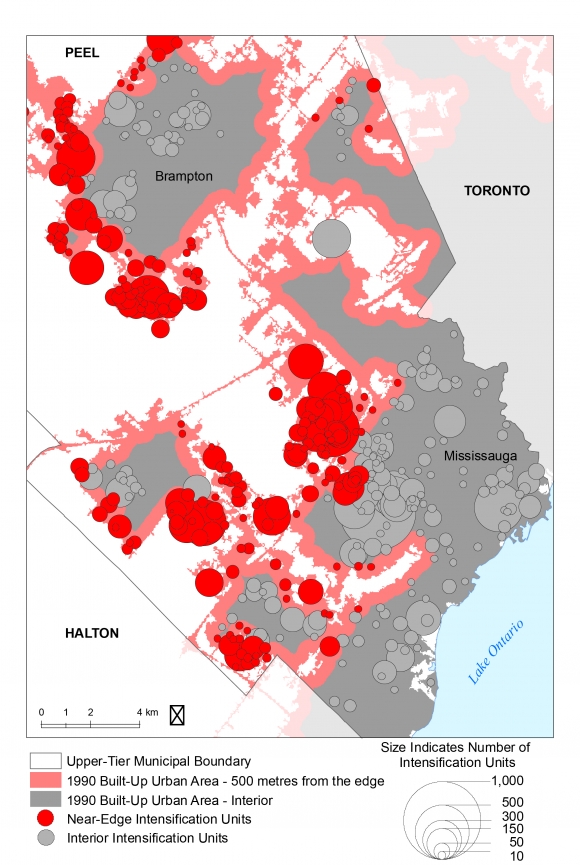

The 40% residential intensification target does not distinguish between effective and ineffective intensification with respect to the Plan's goals. As a result, it is an unreliable measure of progress toward the goals of the Growth Plan. The research shows that between 1991 and 2001, outside the City of Toronto, approximately half of all units constructed within the existing built-up urban area (i.e., those considered intensification) were located within 500 metres of the urban edge. Development of this sort is presumably the product of many factors such as the changing of greenland designations, leapfrogging and backfilling, the market, and the way the approvals process functions. However, development near the edge of the built-up urban area represents a particularly ineffective type of intensification. [See Fig. 6.]

Figure 4: Intensification rates in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, 1991-2001

Fig. 5: The potential impact of achieving the Growth Plan's intensification target

If 24% of all dwelling unit growth in the Greater Golden Horseshoe outside the City of Toronto is in the form of intensification already, then achieving the 40% target would result in only 16% of all units built outside of Toronto shifting from greenfields to the existing urban area over the 30-year period -- about 227,000. Given that the 40% target is slated to come fully into effect only in 2015, halfway through the plan period, the number of units actually diverted is likely to be lower.

The green and beige wedges of the pie indicate units that would be in the form of intensification or on greenfields regardless of the Growth Plan. The hatched area indicates the proportion of units likely to be diverted from greenfields to intensification as a result of the Growth Plan.

Note: In its "current trends" scenario, the Growth Outlook for the Greater Golden Horseshoe projects an increase of 1,721,000 dwellings across the Greater Golden Horseshoe, 1,421,000 of them outside the City of Toronto.

Fig. 6: Effective and ineffective residential intensification in Peel Region, 1991-2001

About 50% of so-called residential intensification that occurred between 1991 and 2001 in the Greater Golden Horseshoe was within 500 metres of the edge of the built-up urban area. The map shows the built-up urban area as it was in 1990 for south Peel Region. Land within 500 metres of the outside edge of the urban area is shown in light red; the interior urban area is shown in grey. The circles indicate the approximate location and magnitude of residential intensification in both the near-edge and interior areas. While filling in holes near the edge of the urban area is a good and likely inevitable part of the development process, it does not represent the kind of effective intensification required to further the goals of the Growth Plan, such as reduced automobile use and more efficient provision and use of infrastructure.

Other measures may be preferable

A more effective approach might be to measure policy outcomes for all types of development. These measures might include the amount and proportion of new population, dwelling units, and office floor space located in designated intensification areas (as measured in Vancouver), the proportion of existing and new population, jobs, dwelling units, and office and retail floor space located within walking distance of higher-order transit within each municipality (as measured in Sydney, Australia), and transportation mode shares within designated intensification areas.

Identifying development opportunities

The Growth Plan focuses on the demand side of the equation -- the expected need for residential dwelling units and the directive to satisfy more of this need within existing urban areas. But equally important is the supply of development opportunities. If the development process is to be predictable for developers and housing affordable for homebuyers, the Province and municipalities should monitor available land and infrastructure capacity for intensification, much as is already done for greenfield development. As the government's technical paper on implementing the intensification rate target suggests, the Province should establish a common set of definitions, standards, and procedures for municipalities to apply when identifying developable and redevelopable parcels.2