Most of the expected population increase will continue to be on greenfields

Despite the emphasis on intensification in the Plan, most new development will continue to occur on greenfields. Even if the Plan's 40% intensification target is met by each upper- or single-tier municipality, this would still leave 60% of future households outside today's existing urban area. In fact, an even higher proportion of future population will likely be located on greenfields, because households in more recently developed suburban areas tend to have more people in them than those in older areas. A Neptis study found that the average number of people in each household in areas developed since 1980 is 26% higher than in areas developed before 1980, and 47% higher than in areas developed before 1960.11

The momentum of current trends will not soon be reversed. Market and development patterns are well established. Much of the land that is designated urban but is not yet built on is already planned and a good portion of it is covered by approved plans of subdivision. These plans are unlikely to be reopened to conform to Growth Plan requirements. As a result, the prevailing pattern of development is unlikely to be significantly redirected in the near future.

Greenfield development should be concentrated

The metropolitan form of the Greater Toronto Area is to a large extent the result of policy. Fifty years ago, the Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board established the policy that outward urban growth would be contiguous. This policy supported the efficient provision of water and sewer lines to the metropolis as it grew rapidly in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The principle was widely admired by other North American regions. The re-enunciation of the principle of contiguous development in the new Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) shows this principle still guides the region's growth.

But contiguity by itself does not produce transit-supportive urban areas. Cost-effective and frequent transit service requires concentrated development. One can see this in the GTA's current suburban areas, which are mostly contiguous, but are rarely able to support frequent public transit service because they lack concentrated nodes of population and employment. The long-standing policy and practice of incremental outward expansion of the urban area along all of its edge without points of significant concentration has allowed for growth to be widely distributed, but has undermined the ability to develop cost-effective public transit. [See Fig 9.]

The Plan's policy regarding "complete communities" and other policies are intended to promote mix of use and urban form conducive to increased transit use, walking, and cycling. But its implementation, if limited to the scale of the subdivision or even the municipality, may not result in concentrations that support larger regional goals with respect to transit use and other outcomes. Only an integrated land use and transportation plan at the regional scale can bring this about.

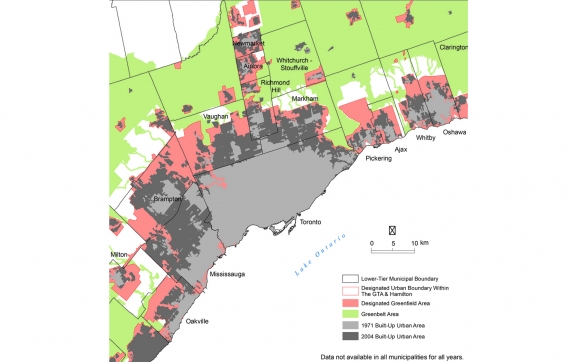

Fig. 9: Outward rings of urban growth, 1971-2004

Over the past 50 years, the GTA has grown through contiguous addition to existing built-up urban areas. The map shows how the outward expansion of the Toronto-Mississauga urban area has expanded to incorporate formerly freestanding towns such as Brampton, Unionville in Markham, and Richmond Hill. The locations of designated future greenfield growth areas, shown in red, illustrate the continuation of the policy of contiguous outward expansion. As this area fills up in the coming decades, there will be pressure to open the band of unprotected countryside between the Greenbelt and the present designated greenfield area for development.

Note: The Growth Plan defines the "Designated Greenfield Area" as the "area between the built boundary and the settlement area boundary," i.e., "lands which have been designated in an official plan for development." Similar to the maps in the Growth Plan, the designated greenfield area in this map does not exclude existing designated natural heritage features. Additional natural heritage features are likely to be designated as part of the forthcoming sub-area assessment process described in the Growth Plan.

The density target for greenfields may not further the Plan's goals

The Growth Plan contains many policies, but few tools by which to measure progress toward their achievement. There is only one target in the Plan that applies to greenfield development. It requires that all designated but not-yet-developed urban land in each upper-tier municipality be built out at an average of at least 50 people and jobs combined per hectare by 2031.12 Instead of requiring that every new development achieve a minimum density, the Plan requires that by 2031, all greenfield development as a whole must meet the target. [See Fig. 10.]

This measure and its target appear to be ineffective and unenforceable. Setting an average density over a broad area certainly permits local densities to be higher in some places and lower in others. But even if the overall target is met, the policy still permits the development of low-density, unconcentrated, non-transit-supportive areas.

Also, the policy may be undermined by long-term trends, such as an expected decline in average household size. Over time, population density will fall as fewer people occupy the same number of dwellings. For the density target to be achieved by 2031, municipalities would not only have to require developers to determine how many people will live in their proposed subdivisions when they are first built, but also in the future.

A similar uncertainty exists for employment. Research shows that jobs "fill in" to new developments more slowly than residents. Over time, the structure of the economy and nature of the labour force change. It is difficult to predict how many jobs will exist in an area, large or small, 20 or 25 years in the future.

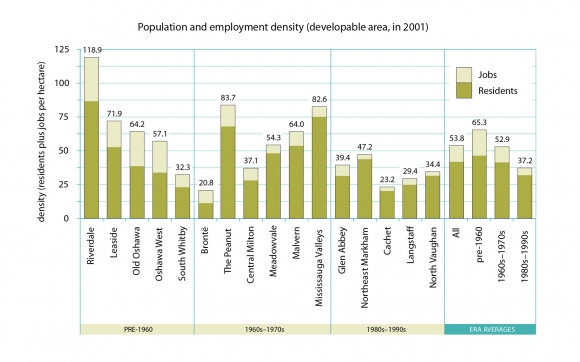

Fig. 10: Densities in the region, 2001

The Growth Plan calls for the designated but not-yet-built urban area of each upper-tier municipality in the region, net of natural heritage systems, to be built out at a density of 50 people plus jobs per hectare as of 2031. The government considers this density to be the minimum required to support basic bus service at reasonable cost.

A study of 16 largely residential, 400-hectare (2-km-square) areas in different parts of the GTA, representing different eras of development, showed that the more recent the development, the lower the population and employment density. The five areas built out in the 1980s and 1990s average 37 people plus jobs per hectare. Research shows that designated employment lands typically accommodate fewer than 40 jobs per hectare. To achieve an overall density of 50 people plus jobs per hectare, densities in both residential neighbourhoods and employment lands would have to increase.

Note: The densities shown are calculated on developable area. Where designated, natural heritage features have been removed from the gross land base.

Other approaches are possible

Policies and targets for greenfield development with respect to density and mixture of uses will need to be clear, effective, and enforceable. To ensure that new subdivisions meet the goals of the Plan, the government might consider other measures. In the United Kingdom, for example, the government has imposed a minimum density requirement of 30 units per hectare for all new subdivisions. [See Fig. 11.] Since the target is applied during the approval process, there is no need to wait until 2031 to find out if the target has been met. Such an approach could be applied in Ontario under proposed changes to the Planning Act, which would permit municipalities to set conditions for development approvals, including specifying minimum and maximum densities and building heights.

Fig. 11: Minimum density requirements for greenfield development in the U.K.

Since December 2002, local planning authorities in rapidly growing parts of the United Kingdom have been required to consult the national government before permitting individual developments of less than 30 dwelling units per hectare. The government has indicated that it will intervene if this threshold is not met. The policy was extended to additional areas in December 2005.13 Between 2001 and 2004, the average density of development on greenfield land rose from 25 to 44 units per hectare.14 By comparison, the residential portions of Leaside and northeast Markham are built out at about 37 and 20 units per hectare, respectively.15

Although the U.K. target has some advantages over the target proposed in the Growth Plan, it does not address employment or encourage mixed-use development. The Province is strongly urged to explore the feasibility of establishing targets for population-to-employment ratios and transit use and develop design guidelines for transit-supportive employment lands.

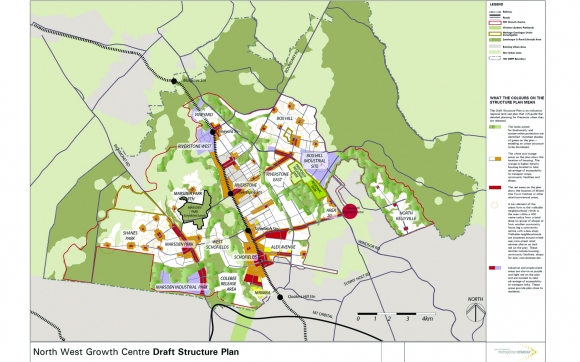

In New South Wales, Australia, the state government, rather than municipalities, manages the process of releasing greenfield land for development in the Sydney region. Under the Metropolitan Development Program, the state studies the potential of areas for accommodating population and employment growth and produces high-level structure plans to which subsequent local planning and infrastructure investment must conform. [See Fig. 12.]