We have seen how the Greater Golden Horseshoe's economy has been transforming in response to competitive pressures stemming from ongoing globalization and technological change.

Does the Growth Plan in its current form address the changing competitive context and spatial economy of the GGH? How could or should the Growth Plan address economic restructuring and promote regional competitiveness? This section addresses these questions, beginning with a summary of the key findings of the analysis.

The GGH's changing spatial economy: key findings

The success of the Growth Plan in achieving key objectives - such as the Urban Growth Centres, compact urban form, supporting a shift to transit, intensification, making efficient use of infrastructure - depends in no small part upon non-residential development. But to date, the Growth Plan has focused primarily on managing residential growth. It has not comprehensively addressed the role of non-residential development in achieving key Growth Plan objectives. Nor has the non-residential element of the Plan been checked to ensure that policies and the spatial vision for the region are grounded in economic reality.

The economic transformation of the GGH presents an opportunity for the Growth Plan to support the competitiveness and prosperity of the regional economy. Urban and regional environments are increasingly central to businesses' ability to compete successfully on a global stage. The Growth Plan could contribute to prosperity with policies that maximize the planning and economic benefits of major investments; encourage built environments that support innovation and networks; and foster an efficient urban form and a regional structure that support transit and labour mobility.

The GGH economy continues to restructure as competitive pressures persist or intensify. The restructuring is often described as a shift from manufacturing to service industries. But the key underlying dynamic is a shift from routine to knowledge-intensive activities.

The shifting economic structure means a shifting regional economic geography. There are clear spatial patterns according to type of activity. Knowledge-intensive activities, such as finance, software creation, or biomedical services, tend to concentrate in a limited number of locations in the GGH. These include Downtown Toronto and the Suburban Knowledge-Intensive Districts (SKIDs). Knowledge-intensive activities have different locational requirements and demands of their built environments compared with more traditional industries; these demands include the quality and character of the work environment, and locations accessible by transit, walking, or cycling.

Other activities, such as construction, manufacturing, or the growing distribution sector, show more dispersed locational patterns, including three suburban employment megazones that dominate the region's economic geography. The biggest of these, the Airport megazone, is the second-largest employment concentration in Canada after Downtown Toronto.

A striking feature of the geography of economic restructuring is the decline of manufacturing across the region, especially in the older industrial areas, which reflects the loss of 200,000 manufacturing jobs since 2001.

How does the Growth Plan address these challenges and opportunities? In the following analysis, we consider our two research questions:

- How is the GGH economy changing and what are the implications of its emerging geography for the Growth Plan policies and spatial vision?

- How can the Growth Plan support the economic competitiveness and prosperity of the Greater Golden Horseshoe?

Addressing the reality of the GGH's regional economic structure

Recognizing and planning for the megazones

The economic geography of the GGH is dominated by significant employment concentrations, including Downtown Toronto and the three suburban megazones: Airport, Tor-York West, and Tor-York East. However, these employment megazones are not recognized in the Growth Plan - neither in terms of their economic role and potential, nor in relation to Growth Plan objectives.

Each of the megazones crosses municipal boundaries, both lower-tier and upper-tier. Because of municipal fragmentation, however, these expansive, auto-dependent, single-use, generally low-density employment areas are not comprehensively and uniformly planned. As a result, they are underperforming with respect to Growth Plan objectives such as compact development, complete communities, and a transit-supportive urban form.

- The Growth Plan policy framework and regional structure concept needs to recognize and plan for the three employment megazones.

A comprehensive plan for the Airport megazone

Despite being the second-largest concentration of employment in the country, the Airport megazone is not even mentioned in the Growth Plan.

- With its municipal partners, the Province could initiate a comprehensive planning and reurbanization strategy for the Airport megazone, aimed at significantly reducing auto trip generation by integrating transit, walking, and cycling access; identifying reurbanization and redevelopment potential; broadening the range of employment uses to support clusters and provide amenities to the working population; and creating flexible, responsive land use planning frameworks.

The relationship between the megazones and The Big Move

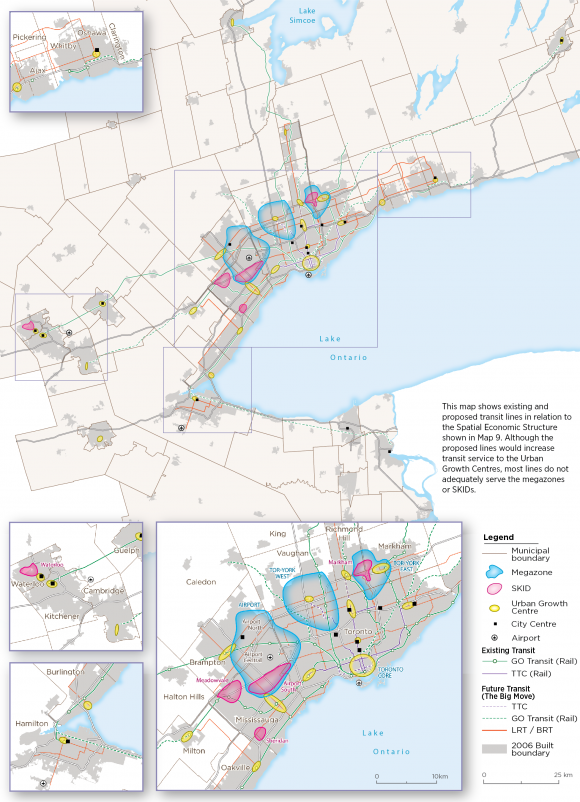

Regional transit planning focuses on the UGCs. But the megazones are likely the single biggest source of congestion in the region, and they are not being adequately addressed by current transit planning. Map 12 shows the region's economic structure in relation to The Big Move plan for transit. This document, first developed in 2008 by the regional transportation agency Metrolinx and since modified, contains the regional goals for transportation in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, including proposed rapid transit lines.

THE MEGAZONES ARE LIKELY THE SINGLE BIGGEST SOURCE OF TRAFFIC CONGESTION IN THE REGION, AND THEY ARE NOT BEING ADEQUATELY ADDRESSED BY CURRENT TRANSIT PLANNING.

Map 12: GGH Structure and The Big Move

The new transit lines proposed in The Big Move plan do not adequately address the employment geography of the region and the primary sources of congestion in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. The plan focuses largely on future, aspirational growth locations, such as the Urban Growth Centres (UGCs), while hundreds of thousands of existing jobs, including many in office uses, remain un- or underserved by transit, especially in the three megazones. Consider the level of transit service to downtown Montreal, for example (68 stations on four subway lines), and compare it with the service contemplated for the Airport district, which has a higher number of jobs.

Recent transit improvements, such as the Mississauga Transitway, and announced plans, such as the Hurontario LRT, will provide some improved transit access to the edges of the Airport District. But the Union-Pearson Express launched in 2015 provides little benefit to the 300,000 workers in the airport area (Kalinowski, 2015).

- The Big Move review presents an opportunity for the close integration of planned transit and existing employment concentrations. An integrated, comprehensive approach to providing transit service to the megazones is needed.

- The tension between expressway investments, which have played a decisive role in shaping the employment geography of the region, and transit investments needs to be carefully considered and resolved in conjunction with the regional structure expressed in the Growth Plan.

The role of Urban Growth Centres

The Growth Plan identifies 25 Urban Growth Centres (UGCs). These are the major element defining the regional structure and the intended focus for denser, mixed-use development and planned transit investment. In the words of the Plan, the UGCs are "to serve as high-density major employment centres that will attract provincially, nationally or internationally significant employment uses [and] to accommodate a significant share of population and employment growth" (Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal, 2006, p. 16).

Map 13 shows the 2011 distribution of core employment as well as the UGCs.

Map 13: Core Employment and the UGCs, 2011

The UGCs can fall into four categories: Downtown Toronto, the other Toronto centres, planned centres in urbanizing cities, and the downtowns of older established cities. Employment data for each UGC is provided in in Table 5[1].

Table 5: Employment in Urban Growth Centres, 2006-2011

| 2011 jobs | 2001-2011 change |

CITY OF TORONTO | ||

Downtown Toronto | 470,400 | 48,000 |

Yonge-Eglinton Centre | 17,445 | 2,080 |

North York | 38,230 | 3,960 |

Scarborough Centre | 13,905 | -950 |

Etobicoke Centre | 8,545 | -1,070 |

PLANNED CENTRES | ||

Mississauga City Centre | 32,575 | 3,870 |

Vaughan Corporate Centre | 2,215 | 155 |

Markham Centre | 7,640 | -5 |

Richmond Hill/Langstaff | 1,840 | 135 |

Newmarket Centre | 3,615 | -310 |

Downtown Pickering | 5,365 | 135 |

Downtown Milton | 3,615 | 845 |

Midtown Oakville | 2,560 | 260 |

OLDER DOWNTOWNS | ||

Downtown Brampton | 6,755 | -3,845 |

Downtown Burlington | 5,375 | -200 |

Downtown Hamilton | 19,260 | -760 |

Downtown Oshawa | 7,695 | 170 |

Downtown Barrie | 5,910 | -170 |

Downtown Brantford | 4,650 | -1,165 |

Downtown Cambridge | 1,795 | -765 |

Downtown Guelph | 6,345 | -770 |

Downtown Kitchener | 11,075 | 365 |

Downtown Peterborough | 8,075 | -1,010 |

Downtown St. Catharines | 7,850 | -1,465 |

Uptown Waterloo | 7,325 | 655 |

TOTALS | ||

Downtown Toronto | 470,400 | 48,000 |

Other City of Toronto UGCs | 78,125 | 4,020 |

Planned Centres | 59,425 | 5,085 |

Older Downtowns | 92,110 | -8,960 |

Source: Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2015).

URBAN GROWTH CENTRES IN THE OTHERWISE FAST-GROWING MUNICIPALITIES SURROUNDING THE CITY OF TORONTO HAVE NOT SEEN MUCH EMPLOYMENT GROWTH TO DATE.

Within the City of Toronto, the UGCs do represent significant, dense concentrations of employment, including Downtown Toronto, North York City Centre, the Yonge-Eglinton area, and Scarborough City Centre. All are centred on higher-order transit.

However, outside Toronto - and Mississauga City Centre, which does have a concentration of employment - UGCs in the rapidly growing suburban areas that surround Toronto do not represent significant concentrations of employment. This includes UGCs in Pickering, Markham, Richmond Hill, Milton, and Oakville. Employment levels in these UGCs pale in comparison with those in the megazones and other employment areas.

Although the Growth Plan was adopted in 2006, most UGCs had been established in regional and municipal Official Plans many years before that date. These include Brampton City Centre, Mississauga City Centre, and Markham Centre. So all else being equal, we would have expected to see growth in these areas by now. However, UGCs in the otherwise fast-growing municipalities surrounding the City of Toronto, which hold the greatest promise in the near term to support the Growth Plan's polycentric regional structure vision, have not seen much employment growth to date.

This fact is illustrated in Map 13, which shows the change in core employment since the adoption of the Growth Plan in 2006. Despite significant core employment growth in these municipalities, most has occurred in auto-dependent business parks and not in the UGCs.[2] In particular, areas in the Airport megazone south of the airport (including the Airport Corporate Centre), as well as business parks in the Highway 404/407 area, Meadowvale, and Waterloo saw substantial employment growth since 2006 - in other words, in the SKIDs (see Table 6).

Table 6: Employment Change in Selected UGCs and SKIDs 2006-2011

MISSISSAUGA |

|

Mississauga City Centre UGC | 3,870 |

Airport South SKID | 3,870 |

Meadowvale SKID | 6,660 |

Sheridan SKID | 1,350 |

MARKHAM |

|

Markham Centre UGC | -5 |

Markham SKID | 635 |

WATERLOO |

|

Uptown Waterloo UGC | 655 |

Waterloo SKID | 4,295 |

Map 14: Employment change and the UGCs

Much of the employment growth in these areas was in financial and business services, which tend to occupy office buildings and thus have the potential to contribute to denser, more transit-supportive urban form.

UGCs in the downtowns of established cities have seen declining employment since 2006, with the exceptions of small positive changes in Oshawa, Kitchener, and Waterloo. Many older downtowns are struggling in the wake of ongoing restructuring of the region, suggesting that the success of transit investments in these locations will require an approach that closely integrates economic development.

Why are many Urban Growth Centres not attracting new jobs?

It is important to understand the reasons behind the lack of employment growth in many UGCs, particularly as these centres are considered key to the success of transit in the region, and to potential transit investments in the billions of dollars.

One set of reasons relates to economic restructuring and the locational preferences of businesses in emerging and growing sectors. We have already noted the tendency of many creative industry firms, as well as finance and business services, to concentrate in dense, mixed-use, accessible urban environments, such as Downtown Toronto. In fact, there is anecdotal evidence of firms relocating from suburban business parks to Downtown Toronto to better attract skilled workers. At the same time, some science-based firms show a preference for suburban business parks over UGCs. Furthermore, the impact of information and computer technologies in slowing the growth (or hastening the decline) of routine, clerical, and back-office uses has added to the lack of demand for suburban UGCs. For many UCGs, especially those without a significant existing critical mass of employment, institutional, public-sector, and population-related office uses will be needed to create a viable centre.

Other explanations have to do with planning and market dynamics. UGCs in suburban areas are competing with office and business parks for development. In general, office and business parks provide cost-competitive locations, with available parking and a permit-ready planning context, providing for relatively certain development timelines and costs. In UGCs, providing adequate parking where transit is not yet in place adds costs that make these locations uncompetitive - especially where structured or underground parking is required. Moreover, in the absence of prezoning that allows for higher densities, office development in UGCs is faced with a longer, uncertain, and more costly planning approvals process.

Finally, attracting development to UGCs is only one-half of the equation. A too-plentiful supply of competing development opportunities in suburban office parks and other locations could undermine the development potential of the UGCs. For example, there are significant office uses, not just in the suburban business parks, but also in many suburban industrial areas. The Tor-York West megazone, for example, which tends to be more industrial than the other two megazones, includes about 20,000 office-type jobs. The Airport megazone and Meadowvale together represent about 75,000 office-type finance and business service jobs (see Table 3, above).

In effect, the Growth Plan itself may be undermining the UGCs: 25 UGCs compete with each other to attract office development, along with 333 Major Transit Station Areas (MTSAs) identified in Official Plans,[3] as well as with intensification corridors, the megazones, and the SKIDs.

- An evidence-based, strategic regional planning approach to office uses is required that is realistically and deliberately integrated with transit planning, and identifies priority office locations. This approach will require a region-wide assessment of future long-term demand for office uses, taking the geography of structural economic change into account, and the potential supply implied by planning policies. Obstacles to development at priority office locations, such as restrictive planning frameworks or financial misincentives could be identified and strategies for overcoming them proposed.

- Planning policy for the UGCs needs to address both demand, by creating appropriate, competitive development opportunities, and supply, by limiting competing opportunities.

Addressing economically significant areas

Strategic employment lands

Lands that are regionally significant by virtue of being associated with strategic industry sectors or clusters could benefit from identification and special designation in the Growth Plan. A regional-scale approach can prevent the overdesignation of lands, usually greenfields, that results from competition among municipalities. Municipalities usually want to keep large sites available in case an important new business or manufacturing operation requiring such a site wants to locate there. However, if all municipalities in the GGH do this, the result is the overdesignation of greenfield lands.

- The Growth Plan could identify strategic employment lands at the regional level, so they can be managed more effectively from a regional land supply and infrastructure perspective, and planning can be better coordinated with regional economic development.

Optimizing existing assets and future investments

The Growth Plan does not contain policies to maximize the economic and planning potential of major investments. There is an important opportunity for the Province to coordinate its many ongoing investments in infrastructure and facilities such as universities, hospitals, or court buildings with planning and economic development. The key is to consider significant investments in facilities and institutions in broader economic and urban terms, in order to realize their potential.

- The Growth Plan could contain policies to strategically locate major facilities to fully leverage their broader economic and urban development potential. In addition, policies could be adopted to coordinate land use, design, planning, and economic development frameworks around major assets.

MUNICIPALITIES USUALLY WANT TO KEEP LARGE SITES AVAILABLE IN CASE AN IMPORTANT NEW BUSINESS WANTS TO LOCATE THERE, BUT IF ALL THE MUNICIPALITIES IN THE GGH DO THIS, THE RESULT IS THE OVERDESIGNATION OF GREENFIELD LAND FOR EMPLOYMENT.

Acknowledging and addressing decline

The Growth Plan is, not surprisingly, focused on managing growth. But the ongoing restructuring of the region's economy also involves decline in certain sectors and locations. The loss of 200,000 manufacturing jobs in the space of a decade is a sharp indicator of the dual-edged nature of globalization. While in some localities, employment in new and emerging sectors is compensating for job loss, some municipalities are suffering job loss without the prospect of new jobs.

- The Growth Plan could identify key areas for strategic reinvestment, including those most affected by restructuring, closures, and job loss, to which future development and investment could be directed. This approach would not only support Growth Plan objectives such as reurbanization, but also support regional economic development.

Reurbanization of employment areas

Although intensification is mentioned in the Growth Plan as an objective for both population and employment, there are no specific policies in the Plan to bring about employment intensification.

Employment intensification in the GGH to date has tended to focus on the intensification of main streets and the redevelopment of brownfields, but the reurbanization of other kinds of employment areas is equally important. There is a tendency to designate new employment lands without adequately taking into account changes in existing employment areas or considering their potential to accommodate growth. Indeed, most municipalities in the GGH are experiencing job loss in their older employment areas at the same time as job growth in newer, peripheral areas. These older employment areas represent a potential supply of employment land that could reduce the need to expand at the urban edge.

Reurbanization of existing employment areas should be a central thrust of the Growth Plan. There are many compelling reasons to promote employment

intensification and the reurbanization[4] of employment areas in the Growth Plan (see text box).

Why reurbanize?

|

A differentiated strategy is called for, since not all employment areas are alike and have similar features or problems. Certain industrial districts, for example, could be replanned to provide more diverse development opportunities to accommodate an evolving industry mix or clusters of related firms. In business parks, the quality of the urban environment could be improved to attract investment and economic activity, make more efficient use of land and other embedded assets, and integrate redevelopment with transit investments. Reurbanization plans must promote the competitiveness of production areas, while avoiding the introduction of destabilizing land uses.

Despite the compelling rationale for reurbanization, current planning tends to be proactive for greenfields development, but reactive - and therefore slow, costly, and uncertain - for development in already urbanized areas. The playing field should be levelled by (1) proactively planning for reurbanization, and (2) putting as-of-right frameworks in place, particularly in economically strategic locations.

- To this end, the Growth Plan could include policies to require municipalities:

- to review their inventory of employment lands to identify priority areas for reurbanization based on their need for renewal, redevelopment opportunities, potential to reduce automobile trips, demand related to long-term economic restructuring, and other criteria identified in the Plan

- to create and implement planning frameworks that facilitate as-of-right development and appropriate urban design frameworks in areas identified for reurbanization

- to report regularly to the Province on their inventory of employment development and redevelopment potential, and track new development on greenfields versus within the urban boundary.

The land supply planning process

The main policies in the Growth Plan that explicitly address competitiveness are those aimed at ensuring an adequate supply of land for employment uses.

The Province creates employment projections for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, currently to the year 2041. Employment growth is then allocated amongst the municipalities in the region. Each municipality undertakes a "land budget" to determine how much, if any, greenfield land must be designated for employment in order to accommodate their allocated growth. Then municipal Official Plans must be amended to reflect the allocated growth and new designations (the "conformity" phase). In fact, a current round of conformity to bring Official Plans into line with recently updated population and employment projections is now under way.

Incorporating the dynamics of economic restructuring in developing employment projections

The current method for forecasting employment in the GGH (Hemson Consulting, 2012) derives total projected employment numbers from population forecasts. Some adjustments are made to reflect structural changes and trends. Employment growth is allocated to four categories:

- population-related

- major office

- "employment lands employment"[5]

- rural-based.

These employment categories are very broad, and mask a great deal of diversity. Our analysis of economic change suggests that each category would include a range of diverse activities, some growing, some contracting; with diverse spatial patterns within the region, and diverse and changing requirements regarding preferred urban environments, building types and location.

The Growth Plan requires municipalities to provide for employment uses "taking into account the needs of existing and future businesses" and the "range and choice of suitable sites." The forecasts do not help much in this regard. And this requirement is not accompanied by any further guidance - based on an analysis of the changing nature of the regional economy and changing locational and work environment preferences - on what those needs might be.

Moreover, the use of very broad categories - especially "major office" and "employment lands employment," sets up a planning process that can lead to planning primarily for only two types of urban production environment when a more nuanced, differentiated approach is needed.

- The Growth Plan employment forecasting approach needs to be reviewed and updated to place more emphasis on the dynamics of change and the economic geography of restructuring in the region, providing more detailed information to inform the planning process.

The geography of demand and the allocation of employment to municipalities

The Growth Plan requires each municipality to accommodate a certain amount of employment growth, based on the forecasts to 2041. Forecasted employment is allocated geographically to municipalities based on planning itself. "The distribution of future employment growth considers where growth is directed through planning and the ability of municipalities in the GGH to accommodate different types of employment."[6]

But demand may not materialize where planning documents and vacant lots suggest, so this directive approach likely overstates the influence of planning over business location. This supply-side approach can also put municipalities at a disadvantage if demand for employment uses does materialize, but their Official Plans do not permit it in the form and location demanded - prompting time-consuming amendments to zoning or plans, or resulting in the proposed development locating elsewhere. The opposite issue also causes problems, if growth is planned for and infrastructure investments made, but employment does not materialize in those locations.

- When allocating forecasted employment to GGH municipalities, the realistic demand for different types of economic activities in different locations within the region should be taken into account, as well as the potential supply of development opportunities.

Land budgets and the geography of economic restructuring

The Growth Plan requires municipalities to accommodate their allocation of forecasted employment by providing an "adequate" supply of lands, and by protecting existing employment lands from conversion to other uses.

The Province's Projection Methodology Guideline, developed in 1995,[7] outlines four categories to be included in the preparation of an inventory of employment lands to be used in establishing land need:

- existing developed employment lands

- registered lots and blocks

- draft-approved lots or blocks

- designated lands with or without an application.

The last three categories generally refer to greenfield sites in various stages of approval. With respect to the first category, it is not altogether clear what types of development or development opportunities are to be considered as contributing toward available supply. Vacant floorspace? Underutilized sites? Vacant sites in the already urban area? What is included will affect the determinations of additional greenfield land needed for employment uses. The issue is of course critically linked to Growth Plan objectives, such as compact urban form, intensification, and the efficient use of land and infrastructure.

The issue is particularly important in the context of the geography of economic restructuring. Do the determinations of land supply need take into account a restructuring regional economy and job loss? Is the land budgeting analysis dynamic, that is, does it consider future land supply opening up on what are today occupied employment lands? The past round of land budgeting could have, for example, entrenched an oversupply of greenfield lands, if deindustrialization was not adequately taken into account.

Map 15 shows designated employment lands, differentiating lands that have been newly designated since the Growth Plan was adopted in 2006. It also shows change in core employment between 2006 and 2011.

Map 15: Core employment change 2006-2011, and employment lands

The map indicates substantial and widespread employment loss in employment lands. At the same time, new employment areas were established in greenfield areas, notably in Simcoe County and the City of Vaughan. While some growing employment uses may not be suitable for existing or older urban areas, such as distribution centres, it is important both for achieving Growth Plan objectives and for economic competitiveness that the amount of employment land needed is not overestimated, and that the geography of economic restructuring is factored into the determination of land uses.

- Economic restructuring, deindustrialization, and other important dynamics of change have important implications in terms of the type and location of land uses and development opportunities that must be planned for, as well as for the potential supply in existing employment areas. The land budgeting process could be reviewed and updated to better account for these dynamics.

The conformity process

The trouble with the GGH employment forecasts is not just the forecasts per se, but how they are used in the planning process. The approach is rigid: regional and single-tier municipalities are given a precise number of jobs and population growth to plan for, in combination with a requirement to provide an adequate supply of land to accommodate the allocated growth.

Lower-tier Official Plans must then be brought into conformity with upper-tier plans, which themselves must conform to the Growth Plan. As of mid-2015, many municipalities still had not completed the Official Plan conformity process.[8] With the Growth Plan review process currently under way, we confront the possibility of initiating the next round of the conformity process before the first round is complete.

Furthermore, if the employment allocation is overestimated for a particular municipality, then too much greenfield land may be entrenched in an Official Plan, undermining Growth Plan objectives for compact urban form. If too little land has been designated, then either a development that exceeds the requirements may have to be forfeited or a lengthy planning process is required to bring it about. This lack of flexibility encourages municipalities to be generous in determining the land needed to accommodate employment in the Growth Plan conformity process, to keep their options open. This may be one reason why the land designated for urbanization in Official Plans as a result of conformity was about equal to the amount the Growth Plan was originally intended to constrain (Allen and Campsie, 2013).

This lengthy and cumbersome conformity process is a problem in and of itself, in relation to costs, flexibility, and responsiveness. It is estimated that auto-dependent suburbs grew by about 380,000 people in just the first five years since the Growth Plan was adopted, in the Toronto CMA alone (Gordon and Janzen, 2013). On the non-residential side, the region may have "benefited" from the fact that development was slow during this period - given the financial crisis of 2008 and ongoing de-industrialization - moderating the demand for greenfield development during that period.

- It may be useful as part of the review of the Growth Plan to explore ways of streamlining the conformity process, and providing options for municipalities to respond flexibly and efficiently to evolving economic demand, while securing key planning objectives.

For example, forecasts might be used as a useful baseline; but informed by more in-depth qualitative analysis provided by the Province of changing industry structure and conditions and drivers of change.

Making planning more flexible and responsive

The question of embedding forecasts in the Growth Plan raises an important broader issue, which is the tension between an increasingly dynamic and evolving regional economy on the one hand and a slow and static planning system on the other. The dynamics of employment uses are more complex and diverse than those of residential development. Firms seek competitive advantage by being responsive to the market, which requires flexible and adaptable production. As well, the integration of the GGH into a global economy can mean more volatility and uncertainty, as we saw with the financial crisis of 2008.

The suggestions provided above, such as employment projections that provide more detail on the changing nature and geography of economic activity, would support more effective planning. But ultimately the best answer lies in finding innovative ways to make planning frameworks and processes inherently flexible and responsive. A critical component is supporting innovative local planning frameworks for production areas that address needs of business, through, for example, urban design and greater flexibility of uses.

DO CURRENT DETERMINATIONS OF LAND SUPPLY TAKE INTO ACCOUNT JOB LOSSES? DOES THE LAND BUDGETING PROCESS CONSIDER FUTURE LAND SUPPLY OPENING UP ON WHAT ARE TODAY OCCUPIED EMPLOYMENT LANDS?

- The Province could undertake to explore and promote innovative planning frameworks and processes that provide greater flexibility and address the needs of GGH businesses.

[1] Figures in Table 5 are from MMAH, n.d., and the source is the National Household Survey Place of Work data.

[2] While the Performance Indicators report (Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, 2015) states that a significant portion of office development since 2006 has located in UGCs and major transit station areas, most of this transit-oriented development has occurred inside the City of Toronto. About three-quarters of the new office space built in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area but outside the City of Toronto - about 6 million square feet - was not located in UGCs, but in auto-dependent suburban business parks.

[3] Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2015), page 10.

[4] The Growth Plan uses the term "intensification" to mean development or redevelopment within the existing urban area. Here we use the term reurbanization to signal a more comprehensive approach to the renewal and replanning of already urbanized areas.

[5] Employment land employment refers to employment "primarily accommodated in low-rise industrial-type buildings, the vast majority of which are located within business parks and industrial areas" (Hemson Consulting, 2012, p. 30).

[6] Forecasts are prepared for each of five "Sub-Forecast Areas." Within each Sub-Forecast Area, total employment is broken down into the four land use categories and allocated by type to municipalities within the Sub-Forecast Area (Hemson Consulting, 2012).

[7] Although the Growth Plan does not require municipalities to use a specific method in developing a land budget (a problem in itself that can lead to inconsistencies), in practice, many use some form of the Projection Methodology Guideline developed by the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing in 1995 (MMAH, 1995). It is cited in section 4.2.1 of Planning for Employment in the Greater Golden Horseshoe as "the current framework for the municipal analysis of land availability."

[8] Revised official plans for the Regions of Durham, York, Halton, Waterloo, and Niagara, the cities of Toronto, Hamilton, Kawartha Lakes, and Barrie, and the counties of Northumberland, Simcoe, Dufferin, and Brant are not yet in effect, either because they have not yet been approved or because they have been appealed in whole or in part to the Ontario Municipal Board (Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, 2015).