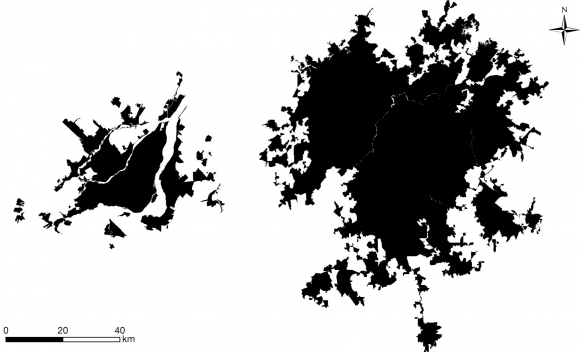

Figure 1: Compact vs. sprawl: Montreal and Atlanta

Many urban regions around the world are working to reduce development on greenfield lands by using land in a more efficient manner and directing new development to already-urbanized areas.

Figure 1 shows two urban regions: greater Montreal on the left and greater Atlanta on right. In 2001, Montreal's population was 3.2 million and Atlanta had a population of 3.4 million in 2000. Although these regions had a very similar population at the time, their urban footprints reflect very different patterns of growth. The urban density in Atlanta at this time was 6.8 persons per hectare; whereas Montreal's urban density was 28.8 persons per hectare. The smaller footprint of the denser city represents not only a less wasteful use of resources, but also a different urban form. Whereas Atlanta has a fairly dense downtown surrounded by mostly low-density suburban development, Montreal's density is more evenly distributed across the urban region.

In Ontario, The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (2006) contains policies designed to contain the urban footprint of one of the fastest-growing metropolitan regions in the developed world. Research has shown that if the Toronto region continues to grow as it has in recent decades, its residents will experience a decrease in their quality of life.1

The Plan is one component of an interrelated package of initiatives that the Province has introduced in the past several years. These include the establishment of the Greenbelt (see the Neptis Commentary on the Greenbelt Plan, 2005), reforms to the Planning Act, the Municipal Act, and the City of Toronto Act, a new approach to capital investment in infrastructure, and the establishment of Metrolinx.2 Each of these initiatives will contribute to growth management in the Toronto metropolitan region.

Notes

1. The 2002 Toronto-Related Region Futures Study found that by 2031, if business-as-usual trends were to continue, the number of automobile trips in the region would increase by 51%, even as transit use declined, resulting in a substantial rise in air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, traffic congestion, and associated costs to citizens, governments, and the private sector. IBI Group in association with Dillon Consulting, Ltd., Toronto-Related Region Futures Study, Interim Report: Implications of Business-as-Usual Development (Toronto: Neptis Foundation, 2002) E23.

2. See Government of Ontario, An Act to Amend the Planning Act (Bill 26), Royal Assent 30 November 2004; Government of Ontario, An Act to establish a greenbelt study area and to amend the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Act, 2001 (Bill 27), Royal Assent 24 June 2004; Government of Ontario, Greenbelt Act (Bill 135), Royal Assent 24 February 2005; Government of Ontario, Greenbelt Plan 2005 (Ministry of Municipal Affairs, 2005); Government of Ontario, Provincial Policy Statement (Ministry of Municipal Affairs, 2005); Government of Ontario, Places to Grow Act (Bill 136), Royal Assent 13 June 2005; Government of Ontario, Places to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal, 2006); Government of Ontario, An Act to Amend the Planning Act and the Conservation Land Act and to make related amendments to other acts (Bill 51), Royal Assent 19 October 2006; Government of Ontario, An Act to revise the City of Toronto Acts, 1997 (Nos. 1 and 2), to amend certain public Acts in relation to municipal powers and to repeal certain private Acts relating to the City of Toronto (Bill 53), Royal Assent 12 June 2006; Government of Ontario, An Act to amend various Acts in relation to municipalities (Bill 130), Royal Assent 20 December 2006; Government of Ontario, An Act to establish the Greater Toronto Transportation Authority and to repeal the GO Transit Act, 2001 (Bill 104), Royal Assent 22 June 2006.