Advocates of the Downtown Relief Line like to recall that the idea of a rail connection between Danforth Avenue and Union Station can be dated back to 1910, even before the TTC was created.[1] The decision in the late 1950s to build an east-west line along Bloor-Danforth instead of Queen took away much of the original function. In the 1970s a second east-west line was proposed as "downtown distributor" for longer lines to northeast and northwest Toronto.

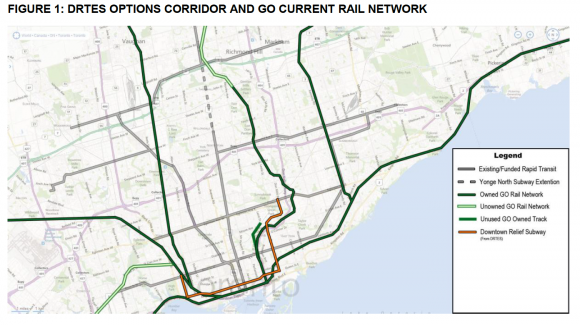

Figure 10: Plan showing proposed DRL and existing GO Rail and TTC subway lines. Source: Metrolinx Relief Line Preliminary BCA, November 2012.

It is only in recent years that the word "relief" has been used, with the implication that the primary purpose of the line is to provide additional capacity into downtown from east and west, providing network resilience and relieving congestion at Bloor/Yonge and on the southern part of the Yonge subway. There will also be improved access to areas east and west of downtown, including the "Kings," Riverdale, and the eastern Harbour, where there is significant development potential. The eastern extension might encourage more intensive development of Don Mills. But these objectives seem to be secondary to congestion relief.

According to the TTC, an "initial phase" DRL from Pape/Danforth to St Andrew would cost about $3.2 billion to build. Costs for the full line, from Don Mills/Eglinton all the way to Dundas West, would be $8.3 billion, plus perhaps $320 million for rolling stock. The initial phase would carry about 11,700 passengers in the peak hour, generating a 4% increase in total rapid transit (subway) ridership. The full line would carry 14,900 in the peak hour, with an 11% increase in overall rapid transit ridership.[2]TTC is not explicit about the year when this level of traffic would be reached, but the suggestion is that it might be in 15 years or about 2028.

With fewer stations than the parallel Yonge or Bloor-Danforth lines, some passengers would have slightly faster trip times, but the actual time saving depends on exactly where they are going in the downtown.

As currently planned, the DRL would not connect directly with GO Rail in the downtown. This shortcoming would limit its "inter-regional" use. TTC has looked at a scheme terminating at Exhibition, to function as a distributor for the Barrie and Georgetown-Kitchener lines.[3] An interchange station with the Richmond Hill line also seems possible at River Street, although there is no mention of this option in any of the DRL reports.

Like the Spadina subway, which was also built as a "relief" line, the DRL would do relatively little to increase all-day transit use or encourage higher-density, transit-oriented development. While some passengers would have faster or less crowded journeys, crowding is only a serious problem in the peaks. So ridership growth seems likely to be small unless the line stimulates more intensive development along its length and not just in the downtown area. This seems unlikely.

Daily subway ridership today is about 1,340,000,[4] so TTC's estimate of a 4% increase implies 53,600 new riders on the Pape-St Andrew Line. This is four times as many new riders as we are assuming would be generated by a GO Relief service from Main and Danforth to Union Station. Some of the new riders would use the Bloor-Danforth and Yonge lines, which would be less crowded than they are today. Some would be generated by new development around stations on the line.

The estimated 11% increase for the longer line implies 147,400 new riders. This line is intended primarily to relieve an existing line. Although there is some development potential, most passengers would have used transit in any case and would not be new riders. Incremental traffic might increase a further 5% to 2033, assuming complementary policies.

These estimates assume the GO relief services are not developed. If they are developed (as described in Chapter 5), with integrated fares from Danforth/Main and Dundas West/Bloor, ridership on the DRL would be substantially less. If GO services to Markham and Richmond Hill are upgraded to offer a "regional Metro" service, and if fares are integrated, then ridership on the DRL will be reduced further.

To estimate the benefits of the DRL, we need to make various assumptions about total ridership, fares, and time savings. See Table A7 in the Appendix for additional details.

Metrolinx says that by 2031, ridership could be 107 million on the entire 13-km line, or about 350,000 per day.[5] Metrolinx has not disclosed whether this estimate assumes upgrading of parallel and competing GO Rail services. Current ridership on the Bloor Danforth subway is about 519,000; this line goes east and west and is longer. Ridership on the much shorter initial DRL from Pape to St Andrew should be less than half this amount, perhaps 160,000 per day in 2023.

As with the GO relief schemes, which serve fairly short trips, we assume revenue of about $2 and auto benefits of $1 for each new transit rider. We also assume passenger benefits of $1 for all riders, not just those diverted.

Notwithstanding some fairly optimistic assumptions, our analysis indicates that benefits are only about two-thirds of the costs, even for the shortest scheme. Put simply, the scheme in its current form is not worthwhile, costing more than it delivers. However, incremental revenues appear to cover incremental operating costs. This fact could explain why TTC supports the scheme; if the capital cost can be covered, TTC will make a profit on the operations.

The case for the scheme would be further eroded if GO is upgraded. As we have shown, GO relief and express rail services, with interchanges at Danforth/Main, Kennedy, Kipling, and Bloor/Dundas West, can provide similar relief to the subway at a fraction of the cost. Although TTC seems not to have pursued the potential of GO relief services, in the 2012 Downtown Rapid Transit Expansion study[6] TTC did consider the alternative of a "Lakeshore RT" service along the GO rail line, with a station at Danforth, but apparently with no interchange to the subway, and with average speeds reduced to 40 km/h,[7] about the same as the subway. Perhaps not surprisingly, TTC concluded that this scheme would not relieve demand on the Yonge subway south of Bloor.

The DRL seems to us to be a scheme whose time has not yet come, if indeed it ever will. Upgrading of the GO rail system would do much more to make the entire GTHA a "transit metropolis," at a fraction of the cost.

Metrolinx seems to be thinking on similar lines. Although the DRL was included in the $36-million Big Move program, Metrolinx has never issued a detailed Benefits Case Analysis. A "Relief Line Preliminary Benefits Case Analysis," dated November 2012 was finally released September 2013. The document provides few hard numbers, with no indication as to gross or net benefits.