Juxtaposing high-density residential development with retail

As high-density, often high-rise, apartment buildings transformed the residential development scene from the late 1950s, planners tried to link these structures to retail areas. This policy was adopted by Metro Toronto and its municipalities and spread throughout the metropolitan region. A testimony to the success of the policy is the proximity visible today between high-density residential and commercial areas, many of which are located at the intersections of arterial roads. The Toronto residential landscape, characterized by low-density neighbourhoods punctuated with pockets of high density, is in large part a legacy of this policy.

The juxtaposition of residential density and retailing was intended to reduce residents' reliance on driving for shopping, while making shopping more convenient for apartment residents and providing a nearby market for stores (Metro Toronto, 1966: 35; 1967: 14; 1979: 3; Scarborough, 1978). These principles still guide the location of high-density housing in suburbs currently undergoing development such as Oakville or Whitby (Oakville, 1991: 46; Whitby, 1999: 22-3). This juxtaposition, however, often failed to provide a pedestrian-friendly environment, because of the wide arterial roads and large expanses of surface parking encircling shopping malls. Still, pathways connecting residential to retail areas were sometimes added to provide facilities for pedestrians.

Master-planned communities

Suburban master-planned communities of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s -- Don Mills, Bramalea, Erin Mills, and Meadowvale -- were structured around focal points, ranging in a hierarchy from convenience shopping at the local level to large (sometimes regional) malls surrounded with office space and high-density

residential developments (see Mississauga, 1968). The existence of this rigid hierarchy, in which centres of various importance were positioned to coincide with markets suitable to their size, was a major feature distinguishing master-planned communities from conventional suburban development. The plan for Meadowvale described its two major centres in this way:

The vitality and variety of Meadowvale's active community life will be focused in two distinctive centres. All paths in Meadowvale will converge on these town centres ... to draw the community to its downtown cores and to communicate the spirit of the community among the greatest number of its residents.

The two centres are designed as shopping-commercial-entertainment--cultural complexes. They are intended to produce aesthetic marketplace environments that are not only efficient, but stimulating and uplifting. Higher--density housing located near the town centres will assure a lively atmosphere throughout the day and evening. (Markborough Properties, n.d.: 17).

As a rule, these centres in master-planned communities were better designed than retail areas near high-density residential districts in more conventional forms of suburban development. The centres expressed architectural sophistication and had more pedestrian pathways connecting them to surrounding neighbourhoods. Still, it would be difficult to describe these areas as truly pedestrian-friendly, because of the large surface parking lots surrounding the shopping centres.

There are important differences between the juxtaposition of high-density residential development and the major centres of master-planned communities, on the one hand, and the nodal strategy that took shape later on, on the other. Residential-retailing juxtapositions and major centres were conceived as activity cores for residential areas, in the neighbourhood unit tradition, whereas nodes emanated from metropolitan structure issues (Perry et al., 1929). Still, these first initiatives marked early attempts at mixing activities and raising densities within suburban settings and encouraging pedestrian-based synergies, objectives that also characterize nodal strategies.

Development along subway lines

To encourage the use of Toronto's subway, planners proposed high-density mixed-use development along the lines and around the stations. This was notably the case along the Bloor-Danforth line, because density along the route at the time it was built was deemed insufficient to justify its existence. In the end, while some stations were the focus of high-density residential developments -- Main, Victoria Park, and High Park, for example -- it proved difficult to intensify the Bloor-Danforth line largely because of forceful opposition from residents living near the stations.

Throughout the subway system as a whole, only a few stations experienced important growth. Among these, the two stations located at Yonge and St. Clair and Yonge and Eglinton stand out by the wide range of functions they attracted and the early occurrence and importance of redevelopment (Lemon, 1985: 143). For example, in 1963, Procter and Gamble announced the construction of its Canadian headquarters on St. Clair Avenue at Yonge Street (Globe and Mail, 10 January 1963: 5). The Yonge-Eglinton area was later successful in attracting a large mixed-use complex.

Yonge-St. Clair and Yonge-Eglinton were the two Regional Commercial Centres identified in the 1969 City of Toronto official plan. These centres were intended to attract office development and high-density housing (Toronto, 1970). Redevelopment around these stations took place within the existing grid. Commercial buildings tended to front directly on sidewalks, while apartment structures were often set back behind a landscaped front yard. Overall, new developments respected the pedestrian-friendly nature of the pre-existing environment and fostered a high level of transit use. These two centres are now defined as mature nodes.

Metropolitan Toronto and Region Transportation Study (MTARTS)

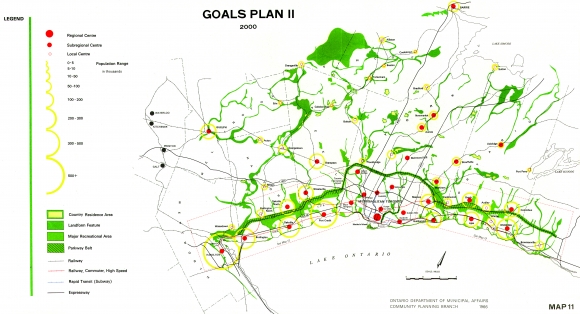

An early version of the nodal concept appeared in 1967 with the publication of the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Transportation Study or MTARTS (Ontario, 1967), begun in 1962. The plan presented metropolitan-wide transportation proposals to improve accessibility in a rapidly growing region. It contained ambitious proposals for both expressways and rapid transit networks. The document also advanced a hierarchy of centres. The first tier consisted of downtown Toronto; the second tier was to include sub-regional centres. In some cases these would be created anew, while in other cases, they would arise from a consolidation of existing suburban central business districts. The document cited the Oakville CBD as an example of this second category of sub-regional centres. (See Map 1.)

Map 1: The hierarchy of centres in the MTARTS study, 1967

Sub-regional centres were defined as follows:

These are the centres that functionally lie between the regional centre at downtown Toronto and the various categories of neighbourhood and community or town centres. In a complex of 61/2 million people they have a critical role to play. They are means of bringing closer to home the wide range of services -- marketing, government, community, social and recreational -- that require a service base that is greater than the 20 to 25,000 persons in 4 or 5 neighbourhoods served by a typical community centre, but not as great as the multi-million population of the regional centre that has both national and international roots... (Ontario, 1967: 30).

The document went on to stress the retail and employment role these centres would play. It also underscored the need for coordination between sub-regional centre and transportation planning. From a transportation perspective, it defined the sub-regional centre as "the hinge between the (regional) centre and its service areas" (Ontario, 1967: 30).

The plan did not provide any guidelines for the layout and design of these centres. They were introduced essentially as a metropolitan-scale planning concept, meant to structure metropolitan development, especially in the suburbs, and reduce transportation demand by bringing employment, retailing, and services closer to housing. Although the plan was primarily focused on transportation and metropolitan form, and was not entirely clear on the planning role of sub-centres, it was the first to introduce this concept as part of a metropolitan-wide development strategy.

This land use concept had even less influence on Toronto metropolitan region planning than the transportation proposals, which far exceeded implementation capacity. No new sub-regional centre was launched as a result of the MTARTS plan. The creation of the sub-regional centres that were then in existence preceded the formulation of MTARTS.

Definitions of nodes and of their antecedents in Toronto

Mid-1960s, Meadowvale Development Plan: Meadowvale Centres

"The two centres are designed as shopping-commercial-entertainment-cultural complexes. They are intended to produce aesthetic marketplace environments that are not only efficient, but stimulating and uplifting. Higher-density housing located near the town centres will assure a lively atmosphere throughout the day and evening." (Markborough Properties, n.d.: 17).

1967, Metropolitan Toronto and Region Transportation Study (MTARTS): Sub-regional Centres

"These are the centres that functionally lie between the regional centre at downtown Toronto and the various categories of neighbourhood and community or town centres. In a complex of 61/2 million people, they have a critical role to play. They are means of bringing closer to home the wide range of services -- marketing, government, community, social and recreational -- that require a service base that is greater than the 20 to 25,000 persons in 4 or 5 neighbourhoods served by a typical community centre, but not as great as the multi-million population of the regional centre that has both national and international roots..." (Ontario, 1967: 30).

1981, Metro Toronto Official Plan: Major Centres

"a) multi-functional in land use; b) compact and pedestrian oriented in their internal organization and design; c) intensive in their development relative to those areas which are not centres. Activities encouraged should include but not necessarily be limited to the following: retailing, offices, hotels, theatre, library, post offices, government and community activity while also serving as transportation hubs for local surface transit." (Metro Toronto, 1981: 22)

1990, IBI Greater Toronto Area Urban Structure Concepts Study: Concept 3: Nodal

"An intermediate concept in which residential and employment growth occurs primarily in and around various existing communities in a compact form, resulting in reduced consumption of underdeveloped land relative to Concept 1." (IBI Group, 1990c: 4)

1991, Office for the Greater Toronto Area, Report of the Provincial-Municipal Urban Form Working Group: Nodes

"A node is an area of concentrated activity serving as a community focal point and providing services or functions not normally found elsewhere in the community. To work well, everything in a node should be close to everything else. This helps promote a pedestrian oriented environment by ensuring walking distances to and from public transit are reasonable. Towards the edges of the nodes and corridors, densities would gradually decrease and give way to surrounding lower density areas, feeding into the transit system and other community services and facilities that will gradually develop." (OGTA, 1991: 19)

1991, North York Official Plan: City Centre

"It is the policy of Council to develop one major centre to function as the prime business, government and community focal point within North York. It is also intended to serve as the transportation hub for transit. This centre is to be multi-functional in land use, pedestrian oriented internally, and should include complementary recreational and residential uses. In general, it is intended to function as the city core or downtown for North York and function as a Metropolitan Major Centre." (North York, 1991: A-6)

1994, Town of Markham, Central Area Planning District Secondary Plan: Central Area Planning District

"The Central Area Planning District is planned as a mixed use, intensive urban area incorporating housing, employment and retail facilities, recreational, cultural, major institutional and civic buildings to serve as a focus for Markham's many communities. The District will be a major activity centre which will be transit supportive as well as attractive and comfortable for pedestrians and will integrate a high standard of urban design with existing natural features to create a unique destination." (Markham, 1994: 15)

1994, City of Mississauga, City Centre Secondary Plan: City Centre

"Goal: Develop a strong mixed-use centre that will be a regional focal point and give a distinct identity to Mississauga. Objectives:

* To provide an area of appropriate size and location for the principal focal point of retail, office, cultural, and civic facilities.

* To provide opportunities for closer live/work relationships and accessibility to amenities and services in the City Centre.

* To design a centre which will facilitate and attract a high level of social activity both day and night, have an attractive visual quality, and a strong sense of identity.

* To create a visual identity for the City Centre by encouraging distinctive architectural themes for the built environment.

* To provide transportation facilities which accommodate trips to the City Centre from other areas of Mississauga and the surrounding region.

* To ensure the best use of existing and planned infrastructure.

* To encourage a range of housing types and sizes, including assisted housing, to meet the needs of the various socio-economic groups." (Mississauga, 1994: 13)

1994, Metro Toronto Official Plan: Major Centres:

"It is the policy of Council that Area Municipal plans and zoning by-laws shall require that the Major Centres...:

a) comprise a mix of uses with a concentration of employment activities and residential uses in a compact, high-density, urban form serviced by high capacity rapid transit. The development of a Major Centre should improve the overall housing/employment balance within the existing local area with the aim of moving this balance towards 1.5 residents per job over time. This ratio is not intended to be applied on a site by site basis;

b) range in size from 50 to 150 hectares;

c) be planned for at least 25,000 jobs to create concentrations of employment sufficient to promote a high degree of transit use. In this regard, the figures for the minimum employment levels set out in Table 2 are intended as guidelines, rather then requirements, for planning infrastructures and other services provided by the Metropolitan Corporation and Area Municipal detailed land use policies; and

d) constitute a focus within Metropolitan Toronto for residents and visitors by including a wide variety of government, institutional, retail, cultural and recreational uses, and both public and civic buildings." (Metro Toronto, 1994: 12)

2002, Toronto Official Plan: Centres

"The Scarborough, North York, Etobicoke and Yonge-Eglinton Centres are places with excellent transit accessibility where jobs, housing and services will be concentrated in dynamic mixed use settings with different levels of activity and intensity. These Centres are focal points for surface transit routes drawing people from across the City and from outlying suburbs to either jobs within the Centres or to a rapid transit connection...

The potential of the Centres to support various levels of both commercial office growth and residential growth outside of Downtown is important. This Plan envisages creating concentrations of workers and residents at these connections, resulting in important centres of economic activity accessible by transit.

Building a high quality public realm featuring public squares and parks, public art, and a comfortable environment for pedestrians and cyclists, is essential to attract businesses, workers, residents and shoppers." (Toronto, 2002: 17-18)

2006, Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe: Urban Growth Centres

"Urban growth centres will be planned --

a. as focal areas for investment in institutional and region-wide services, as well as commercial, recreational, cultural and entertainment uses

b. to accommodate and support major transit infrastructure

c. to serve as high density major employment centres that will attract provincially, nationally or internationally significant employment uses

d. to accommodate a significant share of population and employment growth." (Ontario, 2006: 16)