The key drivers described above are reshaping the makeup of the GGH economy - the concentration of capital, globalization, technological change, and automation. Within this context, certain factors become critical to firms' ability to compete, emphasizing the increasingly important roles that urban environments play in innovation, agglomeration economies, and access to labour. Together, these factors shape the emerging economic geography of the GGH.

As we look forward, key drivers of change such as innovation and automation are evolving, and newly emerging drivers, such as increasing trade in services, will play an important role in shaping the evolution of the GGH economic landscape. These evolving drivers and their potential implications for the region are outlined below.

Innovation

Innovation has become more important to the GGH economy in recent years. Innovation has led to entirely new industries, such as software development and web and app design. But it is also reshaping more traditional industries. In the auto sector, General Motors announced 1,000 new software and engineering jobs in the GGH in the areas of Autonomous Vehicle Software and Controls Development, Active Safety and Vehicle Dynamics Technology, Infotainment, and Connected Vehicle Technology.[1]

Some of these jobs are to be located at the existing Oshawa Tech Centre, but 700 positions will be created at the Canadian Technical Centre, which opened in early 2018. Interestingly, the Centre is located in Markham near Warden Avenue and Highway 7 - an example of science-based activities drawn to a suburban setting. And while Campbell's Soup announced the closing of its manufacturing operations in Etobicoke, it also stated that it would retain 200 corporate and commercial jobs at a new location in the Toronto area, to include a food innovation facility.[2]

The future prosperity of the GGH will not involve attempts to regain low-wage jobs in traditional sectors; continued economic growth places innovation at the core. The success of individual firms and of the regional economy as a whole will depend in large part on the degree to which GGH firms, workers, and institutions can innovate with new or improved products and processes.

As the role of innovation expands, land use planners can respond by ensuring not only that sufficient space is available for these activities, but also that the urban environments created have characteristics that support innovation. What this might mean is discussed in Chapter 5.

Automation

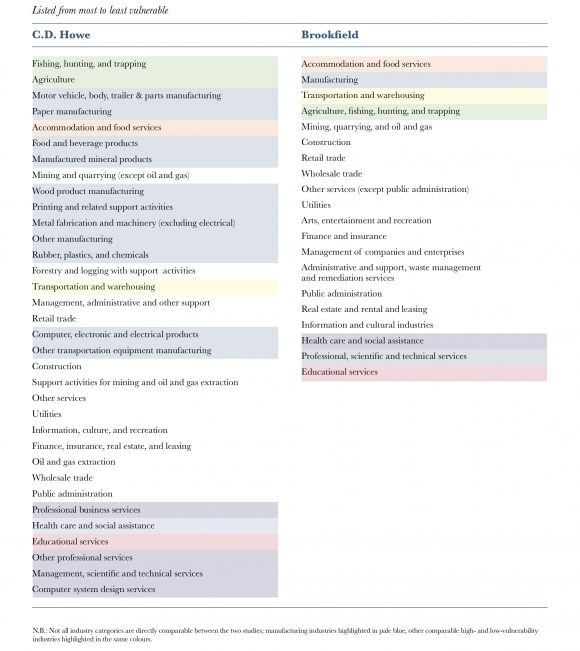

Based on currently available technologies, a Brookfield Institute study found that for Canada as a whole, 46 percent of work activities (equivalent to 7.7 million jobs) were technically automatable. Not surprisingly, there is considerable variation by industry.[3] Both the Brookfield study and a study by the C.D. Howe Institute[4] analysed how the impacts of automation might vary by industry. The results are summarized in Table 1.Until now, automation has focused on routine tasks, such as the use of robots on assembly lines, personal computers to replace clerical and bookkeeping tasks, or ATMs to replace bank tellers. Non-routine tasks - both physical (such as personal care workers, cleaners, drivers) and cognitive (such as lawyers, engineers, designers) have to date been resistant to automation. With advances in computing technologies, sensors, and artificial intelligence, however, the possibility for non-routine tasks to be automated is becoming much more tangible, immediate, and widespread.

Though the methodologies and industry categories vary somewhat between the two studies, there is broad agreement that the industries most vulnerable to automation in the GGH are:

- accommodation and food services;

- manufacturing;

- agriculture;

- transportation and warehousing.

Similarly, both studies found that the industries least vulnerable to automation were:

- educational services;

- professional, scientific and technical services;

- health care and social assistance.

Table 1: Two studies on industry vulnerability to automation, Canada

Automation, restructuring, and the evolving GGH economic landscape

As the impacts of automation are not evenly distributed across industries, so too they are not evenly distributed across the economic landscape.

The Brookfield Institute study also examined the level of vulnerability of urban areas to automation, based on their industry makeup.[5] Figure 3 shows their findings for southern Ontario Census Agglomerations and Census Metropolitan Areas, including those in the GGH. The map uses a location quotient to represent the level of vulnerability to automation, relative to Canada as a whole. An LQ greater than 1 (shown in pink) means that the municipality is more vulnerable than the national average. Blue indicates vulnerability lower than the national average.

Figure 3: Susceptibility of Southern Ontario Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations to Automation, 2011

Source: Lamb, Munro and Vu, Better, Faster, Stronger, 2018, p. 6

In general, the cities most vulnerable to automation were found to be the smaller ones, with less diversified economies, and an above-average concentration of vulnerable activities, which in smaller southwestern Ontario cities tends to mean a reliance on manufacturing jobs.

These analyses illustrate the potential for automation to replace jobs or work tasks, that is, the potential for job losses. But these and other studies also point out the potential for automation to create new jobs in areas like software engineering or data analysis that might compensate for any losses, or for existing jobs to shift towards more productive activities.

Technological advancements throughout Canada's history have helped to drive innovation and raise productivity, improve wealth and increase consumption, and give rise to entirely new industries and economic opportunities. As a result, in the long run, technology has often helped to produce more jobs than it destroyed.

Creig Lamb and Matt Lo, Automation across the Nation, p. 2

The upside of automation and therefore its net impacts on employment are not well known, however. Another Brookfield Institute study projected job growth by vulnerability to automation. Net growth for jobs with low vulnerability was estimated at 712,000 jobs in Canada between 2014 and 2024, compared to net growth of 339,200 for jobs at medium risk, and 395,700 for jobs at high risk.[6] However, this analysis was based on an economic scenario that did not take the impacts of automation into account, and noted that high-risk jobs might grow more slowly than the figures suggest.

So, while we have an idea of the potential employment downside of automation by industry, we do not have a good picture at this point of the potential net effects by industry, and the ways in which automation might contribute to further restructuring of the economy. What we know about the potential overall impacts of automation on the regional economy and on the economic landscape of the GGH is therefore limited.

What we can say is that the impacts of automation on particular cities, communities, or employment districts within the GGH will depend on the degree to which (1) vulnerable activities are found there, and (2) new jobs are generated in the same location versus elsewhere in the region, or indeed, in other regions altogether.

In other words, the new jobs generated by automation may require locations and urban environments that differ from the ones in which jobs were lost due to automation.

Depending on the geography of job growth and loss, automation could further reinforce the existing concentration of knowledge-based activities in a select few locations. Areas with a concentration of vulnerable employment will be more likely to change, and may experience net employment decline. Meanwhile, areas with concentrations of jobs that are least vulnerable to automation may be subject to added growth pressure. As the impact of automation rolls out across wider segments of the economy, its effects would be amplified.

In Chapter 4, we provide some clues to the geography of automation-driven change in the GGH, using a detailed, census-tract analysis of the location of employment in the industries that are most vulnerable to automation. We also discuss some potential implications specific to our Archetypes in Chapter 3.

Automation and the demand for buildings and floorspace

In addition to the potential effects of automation on the evolving structure and economic geography of the GGH economy, there is a second area of interest to planners: the potential implications of automation on the demand for non-residential floorspace.

This is another issue for which there is currently a lack of rigorous analysis. However, a few considerations may be helpful to planners.

The impact of automation on the demand for floorspace depends in part on the sector and type of automation. For example, warehousing, logistics, distribution, and manufacturing (work that tends to be routine and manual) will generally be automated with robots, which will generally require as much space in which to operate as a worker. Automation of routine cognitive tasks, such as bookkeeping or secretarial work (and increasingly, non-routine cognitive tasks) is generally undertaken by software, eliminating the worker and the need for work space. This type of automation will affect the demand for office space.[7]

An interesting analysis by CBRE for the United States explored the potential impacts of automation on the demand for office space.[8] It found that across all major office space in the U.S., 18 percent of existing office stock was at risk due to automation. Also, smaller office markets were more vulnerable than offices in larger cities.

Like the other studies, the CBRE analysis examined the potential downside of automation, not the upside. New jobs could compensate for losses due to automation, allowing demand for office space to be maintained in the long term, albeit with shifts in the types of work being undertaken in offices.

However, the CBRE finding that larger office markets and cities are more resilient to automation, and smaller markets more vulnerable, echoes not only the Brookfield findings, but also the broader tendency, noted earlier in this report, for knowledge-intensive activities to increasingly concentrate in the largest cities, and increasingly, within a small number of locations in those cities.

Another important implication of automation for planning is in the industrial sector - in particular warehousing, distribution, logistics, and manufacturing. Jobs in all these industries were found to be highly vulnerable to automation by the Brookfield and C.D. Howe studies. This means a higher-than-average probability of workers being replaced by robots. Leaving output growth or decline aside for the moment, this finding does not, however, necessarily imply a reduced demand for floorspace. It may imply a continued demand for buildings, but with fewer employees (and more robots) per square metre of space. This has several implications for planning, including the amount and location of land needed for these growing activities and their relatively low employment densities, for example, which will be discussed at the end of this report.

Trade in services

When we think of trade, we often think of trade in goods, like appliances and car parts, or commodities, like oil, wheat, or potash. Trade in services, however, is a significant and growing part of the economy. It consists of exports such as financial, management, engineering, computer and information, and travel and transportation services.[9]

Services currently account for about 15 percent of Canadian exports[10] with a value of about $107 billion in 2016.[11] Since 2000, the share of manufacturing exports has been falling, while the services share has been rising, with strong export growth in finance and insurance services,[12] and the information technology service sector, which sells business solutions, software, and entertainment services.[13]

With continued advancements in information and communications technology and the outsourcing of service functions by firms, there is good reason to believe that this shift to trade in services will continue and that services will play an increasingly important role in export growth[14] and the economy as a whole. This implies the growing importance of trade-oriented service industries.

EXAMPLES OF EXPORTED SERVICES * A Canadian company provides management consulting to a company abroad. * A Canadian engineering firm provides services for a bridge-building project abroad. * A Canadian architecture firm designs a building abroad. * A Canadian software program is delivered electronically to customers abroad. * A Canadian television show is sold to a foreign network. |

Identifying traded and tradable services is important. Tradable services are those with trade potential, but not necessarily currently traded. From a land use planning perspective, understanding the geography of tradable industries can help planners anticipate where there may be additional growth pressure in the GGH. Traded services are those that are currently traded are thus more vulnerable to trade disruptions.

In general, there is less analysis of trade in services compared with trade in goods and commodities. Recent research aims to identify which services have the potential to be traded.[15] A U.S. study analysed service industries according to their level of tradability, ranking them with 1 as least tradable, and 3 as most tradable.[16] In Table 2 we show the most tradable service industries, that is, those with a ranking of 2 or 3 (that is, moderate or high ranking).[17]

Some of the key tradable service industries include software; financial investments; scientific research and development services; and film, video, and sound recording industries. There can be considerable variation in the tradability of services under a common industry heading. For example, not all finance and insurance sub-sectors are tradable; it is primarily the financial investments sub-industry that is. This qualification underlines the importance of delving below the 2-digit industry level to understand the dynamics at play.

Canadian service industries that are currently traded can be identified through measures such as the share of jobs in an industry directly linked to exports.[18] As Table 3 shows, Ontario service industries with a share of export-related jobs above the provincial average of about 10 percent (across all industries) include

- architecture and engineering;

- scientific research and development services;

- computer systems design.[19]

Table 2: Tradability of service industries

Level of tradability on a scale of 1 to 3: 1 = low, 2 = moderate, 3 = high. | |||

2-digit NAICS Code | Industry | Score | |

| INFORMATION INDUSTRIES |

| |

51 | Wired telecommunications carriers | 2 | |

51 | Data processing services | 2 | |

51 | Other telecommunications services | 2 | |

51 | Publishing, except newspapers and software | 2 | |

51 | Other information services | 3 | |

51 | Motion pictures and video industries | 3 | |

51 | Sound recording industries | 3 | |

51 | Software publishing | 3 | |

| FINANCE AND INSURANCE |

| |

52 | Insurance carriers and related activities | 2 | |

52 | Non-depository credit and related activities | 2 | |

52 | Securities, commodities, funds, trusts, and other financial investments | 3 | |

| REAL ESTATE AND RENTAL |

| |

53 | Commercial, industrial, and other intangible assets rental | 2 | |

53 | Real estate | 2 | |

53 | Automotive equipment rental and leasing | 2 | |

| PROFESSIONAL, SCIENTIFIC, AND TECHNICAL |

| |

54 | Architectural, engineering, and related services | 2 | |

54 | Other professional, scientific, and technical services | 2 | |

54 | Legal services | 2 | |

54 | Specialized design services | 2 | |

54 | Computer systems design and related services | 2 | |

54 | Advertising and related services | 2 | |

54 | Management, scientific, and technical consulting services | 2 | |

54 | Scientific research and development services | 3 | |

| MANAGEMENT |

| |

55 | Management of companies and enterprises | 2 | |

| ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT |

| |

56 | Employment services | 2 | |

56 | Other administrative and other support services | 2 | |

56 | Investigation and security services | 2 | |

56 | Travel arrangement and reservation services | 2 | |

| EDUCATION |

| |

61 | Business, technical, and trade schools and training | 2 | |

| HEALTH CARE AND SOCIAL SERVICES |

| |

62 | Community food and housing, and emergency services | 2 | |

62 | Offices of other health practitioners | 2 | |

| ARTS, ENTERTAINMENT, AND RECREATION |

| |

71 | Traveller accommodation | 2 | |

| OTHER SERVICES |

| |

81 | Nail salons and other personal care services | 2 | |

81 | Other personal services | 2 | |

81 | Business, professional, political, and similar organizations | 2 | |

81 | Labour unions | 3 | |

81 | Footwear and leather goods repair | 3 | |

| PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION |

| |

92 | Public finance activities | 2 | |

92 | Armed forces, all branches | 3 | |

Table 3: Direct jobs embodied in exports by select industry, sorted by number of jobs, Ontario, 2013

NAICS | INDUSTRY | Direct jobs embodied in exports | Share of all jobs in the industry (%) | |

3362, 33631, 33632, 33633, 33634, 33635, 33636, 33637, 33639 | Motor vehicle parts manufacturing | 36,343 | 53.0 | |

33611, 33612 | Motor vehicle manufacturing | 28,972 | 80.7 | |

5611 | Office administrative services | 27,515 | 57.0 | |

5415 | Computer systems design and related services | 19,691 | 17.4 | |

5413 | Architectural, engineering, and related services | 17,137 | 25.9 | |

3261 | Plastic product manufacturing | 14,389 | 34.5 | |

5614 | Business support services | 14,057 | 26.9 | |

5417 | Scientific research and development services | 11,752 | 45.8 | |

3364 | Aerospace product and parts manufacturing | 11,194 | 79.1 | |

3339 | Other general-purpose machinery manufacturing | 10,901 | 72.0 | |

5416 | Management, scientific, and technical consulting services | 10,494 | 18.7 | |

3343, 3345, 3346 | Other electronic product manufacturing | 10,243 | 71.0 | |

3332, 3333 | Machinery manufacturing | 9,864 | 64.0 | |

3254 | Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing | 8,839 | 55.3 | |

3344 | Semiconductor and other electronic component manufacturing | 6,668 | 91.0 | |

3342 | Communications equipment manufacturing | 6,051 | 80.9 | |

3341 | Computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing | 1,978 | 82.2 | |

| TOTAL OF ABOVE | 246,088 | 36.5 | |

| Total direct jobs embodied in exports, all industries | 673,886 | 9.7 | |

Source: Cansim Table 381-0032 Value added in exports, by industry, provincial and territorial, annual | ||||

Having identified the traded and tradable service industries, we can locate them in the GGH, and understand which areas may be subject to growth or competitive pressures.

One of the defining characteristics of traded and tradable industries is their tendency to concentrate geographically. This relationship between tradability and geographic concentration is so strong that geographic concentration is often used as a means of identifying tradable industries.[20] This pattern contrasts with that of untraded services, which tend to be geographically dispersed, mirroring population distributions.

To the extent that service exports become increasingly prominent in the economy, the pattern of geographic concentration in the GGH may be further reinforced. These services also tend to be more labour-intensive than other traded sectors,[21] such as manufacturing or distribution, and so have implications for commuter travel and transportation investments.

Of course, trade is vulnerable to shifts in policy and politics, as has become apparent recently with events such as Brexit, or the introduction of new tariffs by the U.S. on steel and aluminium. In Chapter 4 of this report, we identify areas within the GGH that are currently most dependent on trade, and therefore are most vulnerable to trade disruptions.

[1] General Motors, "General Motors announces expansion of connected and autonomous vehicle engineering and software development work in Canada to reach approximately 1000 positions," news release, June 10, 2016.

[2] Doherty, "Campbell Soup Factory," 2018.

[3] Creig Lamb and Matt Lo, Automation across the nation: Understanding the potential impacts of technological trends across Canada. Brookfield Institute, 2017, p. 5.

[4] Mattias Oschinski and Rosalie Wyonch, Future shock? The impact of automation on Canada's labour market, C.D. Howe Institute: Commentary No. 472, 2017, p. 13.

[5] Creig Lamb, Daniel Munro, and Viet Vu, Better, Faster, Stronger: Maximizing the benefits of automation for Ontario's firms and people, Brookfield Institute, 2018, p. 6.

[6] Creig Lamb, The Talented Mr. Robot, Toronto: Brookfield Institute, 2016, p. 16.

[7] Timothy Savage, "What do advances in automation promise for U.S. office demand?" CBRE Viewpoint, January 19, 2017.

[8] Ibid. The study assigned occupations to the different types of office buildings, and then applied a seminal analysis of the vulnerability of occupations to automation in order to understand the extent and locational impacts of automation on office space.

[9] Lawrence Schembri, "Wood, wheat, wheels and the web: Historical pivots and future prospects for Canadian exports," remarks by the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada to the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, November 8, 2016.

[10] Schembri, "Wood, wheat, wheels and the web," 2016.

[11] Global Affairs Canada, Canada's state of trade: Trade and investment update - 2017.

[12] Jacqueline Palladini, Spotlight on Services in Canada's Global Commerce, Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada. August 2015.

[13] Schembri, "Wood, wheat, wheels and the web," 2016.

[14] Schembri, "Wood, wheat, wheels and the web," 2016; J. Bradford Jensen, "Global trade in services: Fear, facts and offshoring," Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2011; Stephen Tapp, "The growing importance of services in Canadian trade," Institute for Research on Public Policy (IPPR) Policy Options, August 3, 2016.

[15] Antoine Gervais and Bradford J. Jensen, "The tradeability of services: Geographic concentration and trade costs," Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 15-12, 2015; Jensen, "Global trade in services," 2011.

[16] Jensen, "Global trade in services," 2011. By "tradable," these studies identify industries exporting a service outside the metropolitan area or regional labour market in which the service is produced, and therefore with the potential to export that service abroad.

[17] All of the other 4-digit NAICS codes in the service sector are ranked as 1. We do not show them here given space constraints.

[18] See David Schwanen and Aaron Jacobs, "The NAFTA constellation: which Canadian industries are most vulnerable?" C.D. Howe Institute, 2017.

[19] Based on analysis conducted for this paper. Uses same method and data source as C.D. Howe, but total exports rather than just exports to the United States. Excluded are industries with total direct jobs fewer than those shown in the table.

[20] Jensen, Global trade in services, 2011.

[21] Ibid.