Latest

The author outlines the major demographic trends that are shaping the Toronto region and their implications for planning, public policy, and quality of life. In particular, he focuses on the rapidity of population growth, the aging of the baby boom, the trend towards smaller households and more non-family households, the effects of large-scale immigration, and the widening gap between rich and poor. The spatial effects of these changes are unpredictable, and Bourne argues for flexible policies to respond appropriately to social changes.

Miller and Soberman describe transportation and land use as a "two-way, chicken-and-egg relationship": competitive, high-quality transit can be provided cost-effectively only where land use patterns support such services, but transit-supportive built forms can be built only if transit service is provided. They examine recent transportation trends in the Central Ontario Zone, including increased dependence on the automobile, and recommend a series of "smart growth building blocks," including road pricing to alter travel behaviour and the choice of vehicles, as well as altering transit subsidy programs to reward performance rather than costs, and providing municipalities and transit agencies with new sources of predictable revenue other than property taxes. Finally, they identify the barriers to implementing these recommendations and suggest several short-term measures to deal with congestion, support transit, and slow down urban sprawl.

This report describes and compares three alternative growth scenarios to the Business-As-Usual projections for the Toronto-related Region to 2031. The report does not suggest what kinds of implementation policies are required to direct growth to certain areas; rather, it shows what would happen if policies succeeded in directing where growth should go.

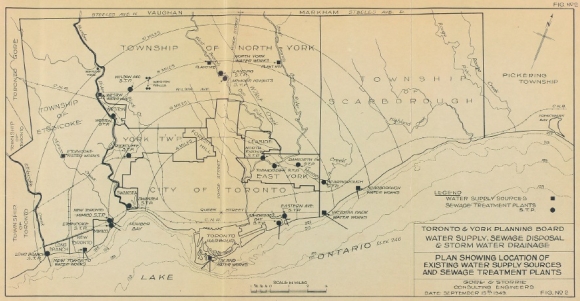

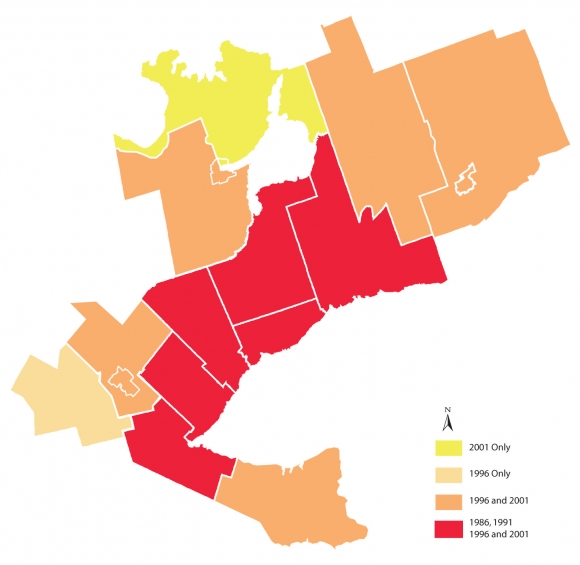

This history of the region's postwar infrastructure planning and construction demonstrates that the maxim "development follows the pipe" has not, strictly speaking, been true over the region's last 50 years, and that in a good many cases the pipe has actually followed development. Where development has followed the pipe, this has been the result of an existing strong development pressure suddenly being relieved by the construction of pipe services. Moreover, contrary to what many people believe today, Metro Toronto's infrastructure expansion was financed with capital borrowed by Metro itself, not with upper-level government subsidies.