Marcy Burchfield, Executive Director of the Neptis Foundation stresses that Metrolinx must not be hijacked by local interests at the expense of the regional public interest in her op-ed piece that appeared in the Toronto Star on April 4, 2014.

Read below:

Once again there is a growing despondency over the fate of transit-building in the Toronto region, triggered by Premier Kathleen Wynne's announcement that HST and gas-tax hikes - proposed by the Transit Investment Strategy Panel she appointed - would not be used to fund public-transit expansion in the GTA.

Meanwhile, heated debates continue in the City of Toronto on whether to use precious funds for subways or Light Rapid Transit (LRT), as many municipalities in the rest of the region wait to see if and when they will be invited to the transit table.

The province intends, in its spring budget, to outline how it will fund Metrolinx's next wave of Big Move projects. But a public weary of political pet projects, endless debate including the sudden switch from LRT to subway in Scarborough, followed by seeming hesitation on funding, could be forgiven for wondering just how things might improve.

Six years after the adoption of the Big Move plan, we must ask: how did we get into this situation?

Metrolinx was created as our one regional entity to consider the big picture. It was intended to take the lead and rise above local squabbles, deal with region-wide congestion and develop an integrated regional transit network.

But the Transit Investment Strategy Panel noted in their discussion paper that the Big Move is the result of a "brokered agreement among the regions" (regional and single-tier municipalities). Although compromises are needed, the final selection of projects and their prioritization were not based on comprehensive criteria that would guarantee an integrated regional transit network.

Moreover, as a recent Neptis report reveals, in the years since the Big Move was published, the agency has been less than transparent and thorough in making the case for individual projects. This lack of information is especially noticeable for projects that serve purely local needs and have little prospect of reducing congestion by attracting new riders and taking cars off our highways.

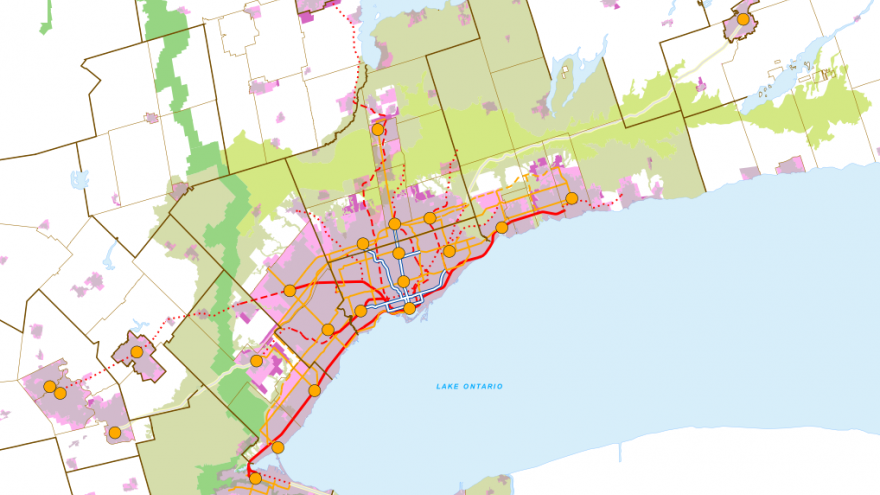

The one project in the original Big Move that would have had a huge regional impact was upgrading and electrifying GO Transit. When Metrolinx was formed, this project was a top priority. Now it has been put on the back burner. And while adding more diesel trains during the day along the Lakeshore route has eased some congestion, it is no way to transform a commuter rail system into a frequent, nimble, region-wide rail network that can become the "backbone" of the GTHA public transit network.

Properly upgraded, electrified and integrated with the TTC system, the GO Transit system could transform transportation in the region and help urbanize auto-dependent suburban centres. As the Transit Investment Strategy Panel noted: "The infrastructure investments we make today will determine the quality of our lives for generations." And the failure to invest wisely will also affect our quality of life - for the worse.

Decisions on transit, like the decision on GO electrification, must begin with evidence-based planning by Metrolinx. The agency must be fully transparent in assessing the value of every single transit project in terms of two crucial criteria: Will it attract new riders to transit? And will it relieve congestion on both existing transit and the road system? Failure to prioritize projects that will see appreciable results could set back the cause of transit in the region for years. Metrolinx must not be hijacked by local interests at the expense of the regional public interest.

We also need to look at international best practices and city-regions that have succeeded in creating networks that attract new riders to public transit and take cars off the road.

Consider Transport for London (TfL), the agency responsible for nearly all transportation planning and operations in Greater London. In the past decade, the London region has seen a spectacular transformation in how people move around - growth of 75 per cent in bus use, 35-40 per cent in commuter rail travel and underground travel and a decline of 10 per cent in auto use - not to mention record high levels of transit service performance and traveller satisfaction.

One reason why the TfL model works is that locally elected politicians provide oversight and give it legitimacy. As a single regional transit planning body, it leads investment, plans routes, fares and schedules, and commissions and funds transit operators to deliver these services.

Another reason for its success is the "seamless whole journey" approach, ensuring integrated fares, smart ticketing, coordinated schedules and comprehensive, real-time journey information across the region and across different travel modes.

We must learn from these and other best practices. Currently, we cannot even come close to achieving the results seen in London and other cities around the world. So the question is: what needs to change?

Perhaps it's time for a "pivot," as they say in the world of start-ups. Metrolinx, for all its good intentions, is in need of a course correction, including a review of its structure, its leadership role and how it can attain legitimacy in the eyes of municipal politicians, local transit agencies, and the public. Metrolinx is still a young organization. There is still time to restructure the agency. We can do better; we must do better.

Furthermore, all political candidates, municipal and provincial, need to look beyond individual transit projects in their wards and ridings and contribute to a productive discussion on how to solve our systemic regional challenges.

Read the op-ed in Toronto Star here.