The proposed amendments to the 2016 Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe represent an important revision of the original 2006 Plan, which aims to curb sprawl and support the economic prosperity of the Toronto region.

Unlike the Greenbelt Plan, which is about where development will not occur, the Growth Plan is about where and how growth will occur across the Toronto region. In that sense, getting the Growth Plan right is critical, as the Greenbelt alone will not stop sprawl.

The proposed amendments - which are open for discussion and comment until 30 September 2016 - include language to manage growth and address issues that were not on the horizon in 2006. These include the Metrolinx Big Move regional transportation plan and the anticipated Climate Action Plan.

In the broadest sense, the proposed amendments show that the province has taken to heart many of the recommendations of the advisory panel for the coordinated provincial land use review [aka the Crombie Panel], which drew on research produced by the Neptis Foundation and others.

Overall, the proposed amendments reflect progressive planning policies and targets, which if implemented fully, have the potential to slow down the outward march of low-density development at the suburban periphery and direct growth to more transit-accessible areas of the region.

However, three things should be kept in mind as one considers the proposed amendments to the Growth Plan.

First, planning is a long-range process. It is important to understand that the proposed amendments apply only to the 2031-2041 planning horizon, which is more than 15 years away. The first phase of Growth Plan implementation has already planned the region to 2031. More than 107,000 hectares of land have already been allocated for future urbanization at lower intensification and density targets and in the context of less ambitious policies than those being proposed today.

Much of that land is still undeveloped, as Neptis research has shown. But without significant changes, the region will continue to expand outwards at much the same densities as we see today for some time to come.

Second, oversights and loopholes that were present in the original plan remain in the proposed amendments. They threaten to let the air out of the progressive policy balloon - especially in Outer Ring municipalities such as Simcoe and Brant Counties, where powerful growth pressures continue.

Finally, a plan is only good as its implementation. The first phase of the Plan was plagued with problems, including appeals of municipal official plans to the Ontario Municipal Board, many of which remain unresolved to this day. These problems can be traced to the Province's abdication of its role as regional planner. It did not monitor the implementation of its own plan and did not provide effective guidance or support to municipalities that needed it.

With the current proposed amendments, questions remain as to whether the Province is not only prepared to "stay the course" - to borrow a phrase used by Minister McMeekin at the launch of the new plan - but also weather the storms that will surely follow during the implementation of the revamped Growth Plan.

WHAT'S NEW IN THE PLAN

First, the good news. Many of the policies in the proposed amendments align with a more sustainable approach to regional planning.

Stringent new requirements must be met before cities and towns are allowed to expand at the urban edge. A new intensification target, which requires municipalities to direct 60% of new development to existing built-up areas - an increase from the current 40% target - could reduce or even eliminate the need for further urban expansion.

The higher intensification target, combined with measures that direct growth to areas with reliable transit in the region (current and planned), will help reduce the region's greenhouse gas emissions.

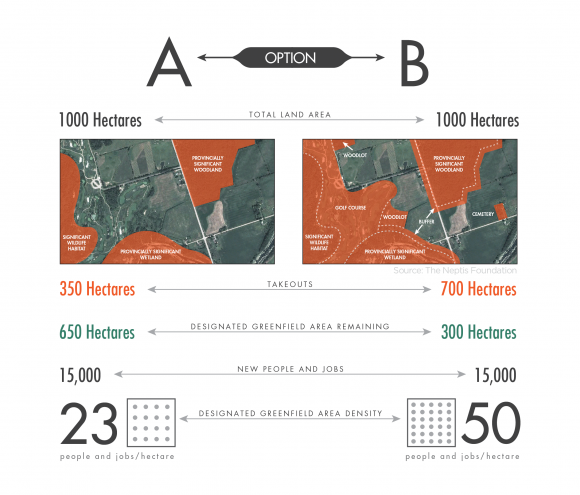

Likewise, density requirements for new developments on "greenfield" areas have been increased to an average of 80 people + jobs per hectare, up from the current 50 [1]. However, this new target may be offset by new rules that specify what can be excluded from a development area for the purpose of calculating density. It is possible that the overall effect on greenfield density target will be minimal, but more research is required to understand this issue.

The Plan also uses new terms, such as "strategic growth areas" and "priority transit corridors" to identify areas where development and transit infrastructure will be integrated and aligned. This is a move away from the more generalized approach to intensification in the 2006 Plan, which directed growth to already built-up areas, but not specifically to locations near transit and other existing infrastructure. The new plan goes one step further by requiring municipalities to update their zoning by-laws in "priority transit corridors" to meet minimum density requirements for the type and frequency of transit service expected in these areas.

The Province has signalled that it will provide guidance on where development will not be permitted by identifying and mapping the natural heritage system and agricultural system outside the Greenbelt. This work will help ensure consistency in how municipalities across the GGH treat these areas in their official plans.

The Province will also ensure greater consistency in planning by developing a standard approach to the process of "land budgeting" - also known as land needs assessment. This is the method that municipalities use to determine how much land is needed (and where) to accommodate future population and employment.

There is a new focus on understanding the impact of development on the region's inland water system and ecology, including aquifers and recharge areas. As municipalities address issues of climate change, it is extremely important to understand the capacity of these hydrological systems and the cumulative impact of development in parts of the Greater Golden Horseshoe that do not rely on the Great Lakes for water takings and sewage outflows.

And finally, there are stronger provisions for integrated watershed planning, supported by fiscally sound decision-making in stormwater master plans, which are required before urban expansion is approved.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED FROM THE LAST 10 YEARS?

We know from experience, however, that good intentions are not enough. In 2006, the Province's ambitious commitment to curbing sprawl and protecting valuable farmland was widely praised, and the American Planning Association (APA) gave the Growth Plan an award. But the fine print of the APA announcement warned that the implementation of the Plan could prove to be its greatest challenge. So it has proved.

A 2013 Neptis Foundation report showed that the Province should have heeded the APA warning. During implementation at the municipal level, the regional plan was compromised in certain ways and many questionable exceptions were made to its provisions. Over 107,000 hectares of land were set aside to accommodate population and employment to 2031. Only 20% of the more than 107,000 hectares was "newly designated land" (that is, designated after 2006). The rest had already been designated for future urbanization in municipal official plans before the Growth Plan was established.

As the 2013 Neptis report showed, many municipalities in the Toronto region continued to plan much as they had in the past. Most municipalities treated intensification and density targets as maximums rather than minimums. Large new developments were approved for areas without fully established municipal water and wastewater services. And when Waterloo Region put forward a bold plan to reduce urban expansion, it had to spend years defending its plan before the Ontario Municipal Board without clear support from the Province.

The most notable exceptions to the Plan were made for Simcoe County, the focus of the first-ever amendment to the 2006 Growth Plan, which remains subject to exceptions and exemptions that apply nowhere else in the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

These exceptions and exemptions include additional population allocations, the creation of four employment districts outside established urban centres, a large and controversial urban expansion north of Barrie in Springwater Township, and the approval of extensive new settlement areas around rural settlements.

Such problems can be attributed to ineffectual guidance from the Province and a lack of commitment to monitoring the implementation of its own plan and, where necessary, defending its principles when they were challenged. Most local municipal Official Plans were appealed to the Ontario Municipal Board - some of these appeals have not been settled as of 2016

WHAT'S MISSING FROM THE PROPOSED PLAN

The proposed amendments to the Growth Plan are aimed at planning for the population and employment that will be added in the Toronto region between 2031 and by 2041. :essentially another 2 million residents and just over 600,000 jobs in addition to the original Growth Plan forecasts. In planning for these people and jobs, municipalities will be expected to prepare new land budgets, in which the new rules will apply - that is, the 60% intensification target and the 80 people + jobs per hectare greenfield density target.

Does the Plan offer municipalities the guidance they need? Three omissions are evident already.

First, the revised Plan does not close the loophole that allows Outer Ring municipalities like Simcoe County and Brant County to use lower intensification and density targets because they (technically) do not have an Urban Growth Centre. In fact, Barrie and Orillia are Simcoe County's functional Urban Growth Centres, even though they are not administratively part of Simcoe County, just as Brantford is the Urban Growth Centre for Brant County. (The problems stemming from this governance anomaly are the subject of a recently published book.)

Because of this loophole, Simcoe and Brant have been allowed to plan at very low densities and threaten to recreate the Mississaugas of yesterday, something that Growth Plan is ostensibly trying to prevent and Mississauga today is trying hard to rectify. Furthermore, in the case of Simcoe County, the province is planning to increase the frequency of commuter trains by upgrading GO commuter rail to Regional Express Rail. This loophole for the Outer Ring circumvents the new Plan's own goal of aligning higher-density development with transit infrastructure investments.

Second, in the Inner Ring, that is, the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, the new plan does not recognize key employment zones, such as the area around Pearson Airport. The airport employment megazone accounts for a significant portion of the region's congestion. As suggested in the Neptis report Planning for Prosperity, this area needs to be planned as an integral employment district, but this has not happened to date because it straddles four municipal jurisdictions. The Growth Plan gives the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing the authority to identify "prime employment areas." So far, this authority has been used only to create future "strategic settlement employment areas" and "economic employment districts" in Simcoe County. The Growth Plan needs to acknowledge and plan for existing regional economic assets in the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

And finally, a framework for monitoring the implementation of the Plan is lacking. In the first phase of Plan implementation, many municipalities did the barest minimum to meet their targets and both municipalities and the Province approved developments that contradicted the vision of the Growth Plan. A robust monitoring program might have prevented these problems. The next round of implementation of the Growth Plan must be more transparent. The new plan gives the Province the ability to request data from municipalities for the purposes of monitoring the Plan's implementation, but little in the Plan requires that this data be made public. Data collection and monitoring is not only necessary for gauging whether municipalities are meeting their targets, but also for understanding the dynamics of change including loss and gain of jobs and population within our region.

TYING IT ALL TOGETHER AND GETTING IT RIGHT

What ties all of this together is a key recommendation from the Crombie panel, which calls on the province to extend the deadline for municipalities to conform with Amendment 2 to the Growth Plan from 2018 to 2021. The extra time, the Crombie panel says, is required to "ensure that necessary provincial guidance and studies, as recommended in this report, are available in time to inform municipal conformity work."

It is not just a matter of extending the deadline for completing revised official plans; the time at which municipalities begin their land needs assessments must also be pushed back. What is required is a halt to the designation of even more new urban land - beyond what already exists - until we figure out the big picture.

Even before the Crombie panel had finished its work in 2015, some municipalities, such as York Region, had begun the process of designating more land under Amendment 2, despite the arguments made by some that its current land supply could last beyond 2031.

Moreover, in York Region, much of the new growth between 2031 and 2041 is being directed to the northern, less developed municipality of East Gwillimbury, rather than the urbanized municipalities of Vaughan and Markham. Yet Vaughan and Markham are the sites of massive investments in transportation - including subways, dedicated Bus Rapid Transit routes, and parts of the proposed $13-billion electrified GO Regional Express Rail network. Vaughan also has the potential of the yet-undeveloped Vaughan Metropolitan Centre, which lies at the end of the Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension, now under construction.

Why the rush? The panel highlighted "key knowledge gaps that should be addressed before further decisions are made about where to grow in the GGH." These gaps "involve studies and strategies at the scale of the GGH and/or the Province, on a range of topics (e.g., the assimilative capacity of lakes and rivers, infrastructure capacity and requirements, prime agricultural lands, natural heritage, water resource systems, transportation and transit infrastructure, housing stock, affordable housing, and climate change)."

The panel also called for "more rigorous and consistent information to assess the performance of the four plans...to enable corrections and adjustments to future growth patterns." The information "would include population and employment figures, land consumption and intensification rates, density of built form, transit development and use, agricultural viability, watershed health and protection of natural heritage systems."

Before more land is designated for urbanization, there are important questions to be answered, such as:

* How much unused water and wastewater servicing capacity is there in built-up areas?

* How much land should be part of an integrated Natural Heritage System beyond the Greenbelt?

* How does support for a prosperous agricultural system in the GGH impact future urban land needs?

* Where are the priorities for extending transit? How can it better serve existing employment zones that are currently car-dependent and causing congestion?

* How can governance be improved so that the work of provincial ministries and agencies and municipal administrations be coordinated to avoid conflict and delay in the implementation of the Growth Plan?

It's critical that the province give clear direction that municipalities must wait until these questions are answered before embarking on a new round of urban expansions. Otherwise, there is the risk of further expensive battles at the Ontario Municipal Board.

We need time to get things right if, in the end, the common goal is to create an environmentally sustainable and economically competitive city-region rather than pursue ad hoc individual interests.

Correction: This Brief has been modified since its original publication. The proposed changes to the Plan will apply to the Growth Plan's original planning horizon of 2031, rather than only to the 2031 - 2041 planning horizon which was introduced by Amendment 2 of the Growth Plan.

[1] Note that the target is an average for each upper- or single-tier municipality; not every single development must meet the target.