The Greater Golden Horseshoe

Government planning and policy development at all levels depend on forecasts for population and employment. Planning for infrastructure investment, land development, and transportation also depend on forecasts about household size and housing requirements.

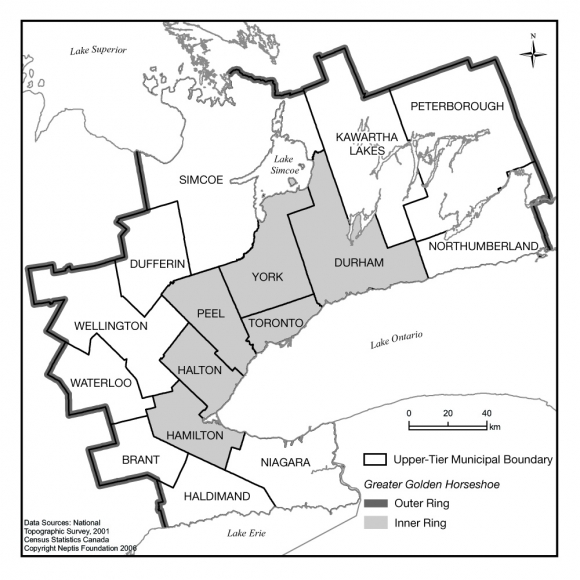

In this report, Will Dunning develops forecasts for population, employment, household formation, and housing demand for Ontario's Greater Golden Horseshoe in the context of economic trends that affect the housing market, immigration and migration, and the size and structure of households.

The housing market is cyclical; periods of intense activity are followed by periods in which housing starts decrease. An analysis of housing starts in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) since 1987 suggests that the housing market peaked in 2003 and is starting a period of decline. At the same time, employment growth in the GTA appears to be slowing, partly because of the weakening of the U.S. dollar, the prospect of rising interest rates, and the retirement or early retirement of baby boomers.

Trends in international immigration and in migration within Canada also affect the region's population and employment prospects, and are themselves affected by employment rates. In the Inner Ring of the Greater Golden Horseshoe (the GTA plus Hamilton), peaks in immigration generally coincide with peaks in employment growth.

Where people settle within the region is strongly influenced by housing prices. People migrate into the region when employment growth is strong, and within the region, choose the areas where housing prices are affordable to them. As housing prices rise in the Inner Ring, people become more likely to choose housing in the rest of the region (the Outer Ring).

Cycles in employment and the economy also affect the kind of housing that people choose. During strong markets, the proportion of apartments rises relative to houses. The share of single detached houses has fallen over the last decade and a half; single detached houses now account for less than half of all housing starts in the GTA. The share of semi-detached and row houses has risen and fallen over the same period; after increasing for several years, they are now losing share to apartments. These changes relate to housing prices: as prices rise, more people choose apartments. Also, the low interest rates of recent years have encouraged many renters to buy condominium apartments.

Given long-term trends in employment and immigration, Dunning projects the population of the Greater Golden Horseshoe at 10.48 million in 2031, compared to 7.88 million in 2001. The figures represent an average growth rate of 86,700 people per year, but the rate of growth will fall over the period, from 109,600 people per year between 2001 and 2011, to 62,000 people per year between 2021 and 2031. This decrease largely is due to the aging of the population, as retirees move elsewhere and mortality increases.

Within the region, the share of growth going to the Inner Ring will fall from almost 70 percent to just above 60 percent, if house prices in the Inner Ring remain at or near present levels.

Over the next three decades, the forecasts suggest that the rate of household formation will slow and household size will decrease from 2.80 people per household in 2001 to 2.53 people in 2031. These trends will affect the amount and type of housing that is needed. Housing starts would fall from an average of 54,800 units per year between 2001 and 2011 to 32,400 units per year between 2021 and 2031. If, at the same time, housing costs and interest rates rise beyond the trend levels that have been assumed, the demand for apartments will increase relative to single detached houses.

The aging of the population will also mean slower employment growth and a lower employment rate. This will be true for the country as a whole, so the trend is unlikely to be offset by migration from elsewhere in Canada, although it could be affected by increased immigration of working-age adults from outside the country.

Finally, Dunning compares his forecasts to those prepared by Hemson for the Ontario government and those by the IBI Group for the Neptis Foundation. His projections for both population and employment growth are considerably lower than those by Hemson and IBI. Dunning predicts 1.1 million fewer people and 700,000 fewer jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe in 2031 than Hemson; and 500,000 fewer people and 800,000 fewer jobs than IBI. The differences stem from differing assumptions about migration and employment growth. Hemson and IBI generally assumed continued robust employment growth, whereas Dunning assumes that sustainable long-term growth rates are lower. He incorporates a falling employment rate due to the aging of the population, which in turn will lead to lower migration into the region.